The Way of Mitchum:

So Manly You Could Even Skip a Day!

Posted By

Peter D. Bredon

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

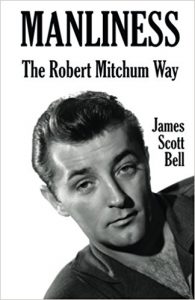

James Scott Bell

Manliness: The Robert Mitchum Way

Woodland Hills, Cal.: Compendium Press, 2016

“A man must defend his home, his wife, his children and his Martini.” — Jackie Gleason

As the direct descendent of one of England’s greatest detectives,[1] [2] I have of course followed with interest the development of the genre, especially the rather more brutal American branch, so different from granddad’s genteel country house affairs.[2] [3]

So when I noticed that bestselling thriller writer James Scott Bell had written a book on manliness, taking noir icon Robert Mitchum (1919–1997) as his lodestar, I grabbed a copy quicker than Hank Quinlan could slap a confession out of a Mexican shoe clerk [4].

Not just another look at the loss and possible return of manliness, this one, rooted in cultural history rather than parental basement and barroom theorizing, could teach the manosphere a few important truths as well.

A pulp writer has got to keep his eyes open, and Bell has noticed some things aren’t right anymore:

We are fast losing something essential in American life—the man who knows how to be a real man; who know how to treat women and children and community; who knows how to fight for what’s right and honorable and who takes seriously his role as warrior and protector and father.

[S]omewhere in the past sixty years that kind of tradition has been ridiculed by those who think there should be no such thing as manliness, that society would be better served by doing away with virtually any word that has ‘man’ in it.

How’s that working out?

It’s a popular topic here at Counter-Currents. Jef Costello makes a specialty of it, even devoting a book to James Bond as an icon of manhood.[3] [5] Even that perennial left-fielder James O’Meara has tried his hand at it.[4] [6] Both have gravitated to the movies, and why not? It’s arguably our most important artistic medium, and it certainly shapes the imaginations of the viewers, especially the young.

Mitchum’s movie roles in particular, all represent to Bell “some aspect of the quintessential American male. Even in films where he assumed the role of villain there is a lesson to be learned — the consequences of violating manly virtues.”

The result is a guided tour through Mitchum’s oeuvre, as the French would say,[5] [7] from timeless classics like Out of the Past (1947; possibly the greatest noir of all), The Night of the Hunter (1955), and Cape Fear (1962) to studio potboilers, TV miniseries (Winds of War), and a few noble failures (Bell suggests Ryan’s Daughter [1970] needs to be re-evaluated).

And along the way we learn lessons: section titles include “A real man refuses to play the patsy.” “A man keeps his word, even if he’d rather not.” “When insulted by a bully, a man stays cool” — “But a man isn’t afraid to get hot when he needs to.” “Once a man takes on a tough job, he doesn’t quit.”

Speaking of patsies, Bell is no sucker for Hollywood guff; he’s not afraid to criticize the advice on offer at the movie theater, even when it comes from John Wayne himself:

When a man really messes up, he apologizes and makes things right

There’s a manly film called She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949, John Ford) starring manly man John Wayne. It’s got manly lessons, but one flaw. There’s a line that Wayne, as Capt. Nathan Brittles, keeps repeating. “Don’t apologize. It’s a sign of weakness.” That’s bogus. A real man apologizes when he messes up, when it’s his fault. He stands up and takes his medicine. He doesn’t make flimsy excuses. And when he really messes up, he shows contrition by trying to make things right.

A lesson so important, Bell thinks we have to learn it twice:

A man apologizes when it’s his fault

Real men apologize when they are in the wrong. They don’t sentimentalize it, they don’t try to manipulate the other side. They say they are sorry and move on. And every now and then [as in The Yakuza [1974]), they show true contrition by cutting off their little finger.

Talk about an apology with some meat to it! The lessons are clear. First, try not to have anything to do with the yakuza. Especially if you’re an American. Second, if something is your fault, apologize and mean it.

All this wouldn’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy, mixed up world of ours if the auteur theory were true, and actors just meat puppets paid to learn lines and not bump into the furniture.[6] [8] But in his opening chapter, Bell makes a convincing case for the effectiveness of Mitchum’s manliness lessons arising from the alchemy between script and the man himself.

The various lessons on marriage and how to treat a lady in general take on authority when delivered by someone whose own marriage lasted until his death, for a total of 57 years.

A man fights to keep his marriage together

Men need to get married. They don’t need to be perpetual boys who impregnate girlfriends and walk away. They need to get married, because that forces them to grow up. We need more grownups. We’ve got enough boys as it is.

Indeed, one can only imagine the sneer of contempt Mitchum would have delivered if he had to contemplate today’s manosphere and its notions of “game” and pick-up artistry.

A real man respects women

Men are naturally sexual barbarians. They have to be restrained either by outside force—such as criminal laws—or inside character, which requires the strong nurture of family, community, or truly peaceful religion (and preferably all three).

But this lesson needs to be hammered into men: your aggressive nature, unleashed, untamed, unmanaged, will result in the mistreatment of women, and you’d better get this straight right now, or your name might end up on a police blotter with sexual offender status slapped on you for life.

A man knows when the time’s not right to flirt with a woman

Some men think they always have to be “on” around women. There are certainly appropriate circumstances in which to flirt. . . . But a man who thinks he always has to put on his flirt face is really evidencing insecurity. Women much prefer a man who knows who he is and what he is about.

No #MeToo trouble for Mitchum men. On the other hand,

By the way, a real man does not ask for permission to kiss a woman. That is only in the doofus rules. A man goes in for a kiss, and if the woman refuses or pulls away, he accepts it with grace. But he does not give her an informed consent form beforehand. (Unless, of course, he is a young man going to college, in which case all the rules have been re-written by chuckleheads.)

Speaking of college,

A man knows how to play poker

When you are a young man, and go to college, the first thing you need to do is find a quiet place to study. The second thing is to get into a weekly poker game.

After all, “Robert Mitchum hardly ever changed expression. It’s a good poker face rule of life. Never let your enemies know what you’re thinking by the wrinkled brow or sweat on your forehead.”

Of course, it’s not all about dallying with the ladies. There’s enough blood and guts to keep Jack Donovan happy:

A man listens to, and properly channels, his warrior heart

Having a warrior’s heart is not all glory and parades. It recognizes the hell of war, but does its duty anyway.

A man knows war is hell, and hell doesn’t make friends

When hell is your enemy, there are not perfect answers. But men have to make a decision. The people in the stands, don’t.

But that’s no excuse for being a brute. Bell points out that

A man knows how to be charming

The nurturing of grace and wit and ease of motion was something men used to strive for.

Today, I see a lot of posing. Guys with default macho walking into bars with unsmiling, hard-ass looks on their faces, as if this is what it means to be cool.[7] [9]

I laugh at them.

Robert Mitchum would have found them boring.

Again, we see the alchemy of man and role; Mitchum himself felt no need to bore us in order to “demonstrate value” or otherwise prove his masculinity. He wrote poetry; he wrote and recorded his own songs, and even came out with an album of calypso [10] (so much for cultural appropriation).

So charming, and so sure of his manliness, that Mitchum, before his big break in The Story of G. I. Joe (1945) could even pull off this kind of scene in Girl Rush (1944):

When Jim is alerted that thugs are waiting in Red Creek to shoot the men and take the ladies, Jim hatches a plan to dress them all in drag. So on they come into town and the men of Red Creek think it’s only the women. They invite them into the saloon. And every one of them is hit on. Since Mitchum is tall and broad in the chest—in a manly sort of way, of course, a tall cowboy comes over and says, “You’re for me, ma’am, I like ’em big.”

Ever the charmer, even in drag, Mitchum replies, “Well, they don’t come too big for me either, bud.” Works like a charm. The cowboy takes Mitchum over to the bar to buy him (her) a drink.

But don’t forget that “broad in the chest” part either. Bell has some advice for the gym rats:

A real man has muscles

A man should be strong physically. This doesn’t always mean bulky. But it does mean strengthening those arms. There was a time when the male ideal included having a certain kind of physique. Robert Mitchum had it. The V shape with broad shoulders and big chest, and muscular arms for heavy lifting. Somehow another shape has gained acceptance in our culture. A sort of creamy smoothness combined with a spindly softness. Metro,[8] [11] not manly. Hipster, not Homeric. A man needs muscles.[9] [12]

Indeed, Mitchum needed muscles; unlike, say, Bogart, he wasn’t born among the WASP aristos; he described his childhood as “broken windows and bloody noses” and later, like Harry Partch [13], he spent the Great Depression hopping freights as a hobo; one result was that even as a star, Mitchum, like Bogart, treated everyone on the set with respect and acted (in both senses) as a gentleman.

Well, a tough-guy sort of gentleman. He was not above teaching a few lessons to his “betters.”

The director, Otto Preminger, was notoriously hard on his actresses, and in this scene he kept directing Mitchum to slap [Jean] Simmons harder, take after take. Finally, Mitchum had had enough, turned around and said, “Like this?” and slapped Preminger! The director stormed off the set and went to producer Howard Hughes and demanded that Mitchum be fired. Um, no. Hughes was not going to fire his biggest star. Preminger was forced to finish the film, and it has since become a cult classic.

Mitchum was lucky enough to have Hughes around on another occasion, right when he was breaking out as a star, when he was busted for marijuana (quite an offense in the days of Reefer Madness); although he told the booking cop his occupation was “former actor,”

Hughes was a risk taker and didn’t like anyone telling him what to do. He also had the keen insight to understand that a little bit of danger was now associated with Mitchum, and that would increase his box office appeal with the bobby-soxers. This was just before the age of Brando and Dean. Indeed Mitchum, one could argue, laid the groundwork for those two iconic bad boys. In any case, Mitchum’s career soared to its greatest heights after his dustup with dope.

Even at the start of his career, when RKO wanted him to change his name to “Robert Marshall,” Mitchum “told the studio bosses where they could stick that idea.”

Mitchum was always his own man, and Bell finds support for his rule that “a man takes a stand for freedom of the individual” in the 1958 Thunder Road, where again man and role are one:

This was a personal project for Mitchum, who came up with the original story, starred (with his son), co-produced, and co-wrote the awesome theme song. A year later, Mitchum recorded the ballad he wrote for the film. You can find it on YouTube [14].

Bell notes that in the film, “Luke transports whiskey in a hidden compartment adjacent to the gas tank. His car also has a button that releases an oil slick, causing the pursuing vehicle to swerve off the road, as in a James Bond film.” Bond and drinking seem to go together (didn’t Fleming get the name from “bottled in bond”?) and Bell of course has a rule for it: “A man who chooses to drink knows that one martini is enough.”

Alas, here he strays out of his area of competence, and proceeds to garble the recipe for a true martini. I suggest you rely on my own countryman, Kingsley Amis on this;[10] [15] interestingly, also a Bond expert. One thing I might add: when Bell advances the “one martini” rule, he neglects the interesting fact that martini glasses — and servings — have increased in modern times. The martini glass of the past was quite small — in North by Northwest, Cary Grant picks up a gimlet when dining with Eva Marie Saint on the train to Chicago and it quite disappears in his hand; and look at the tiny glasses of the ad men he meets at the Plaza Hotel’s Oak Room in the first scene. This is why the businessmen of the Mad Men era didn’t fall down drunk after their “three martini lunches.” Today’s bars justify their $15 prices by the usual expedient of increasing the size (since there’s such an enormous markup already, doubling the amount is a negligible cost), just like the “supersize” portions of fast food.[11] [16]

Altogether, Bell and Mitchum have some good lessons for us as we try to solve the problem of disappearing manliness.

[T]rue manliness is not to be confused with Alpha-soaked testosterone. That is mere pose. It’s not about chest-beating. It’s not about strutting through a room to make sure everyone knows you’re a man. A real man doesn’t need to pose. He doesn’t announce his manliness. He lives it.

But Bell really isn’t one of us, as far as diagnosing the problem goes. The answers proposed on our side or site wouldn’t occur to him, or he’d be horrified if they did. He barely makes out the questions themselves.

Politically, he’s your basic Boomer. Hitler is a bad hombre, full stop (as we Brits say); Roosevelt is a hero — and so is Eleanor. But then the manly men of the ’40s thought so too; manliness — and its opposite — used to be common to men as such, whatever their politics.

He does note that the change in movies seemed to start happening in the ’70s. More generally:

What used to be called ‘manly virtues’ have been dismissed and denigrated over the last forty years or more. This acid drip began (as acid drips usually do) in the halls of academia. Gradually the poison seeped into society at large until denigration morphed into accepted wisdom. But it is the wisdom of fools. For robust manliness is not only necessary for the vitality of America (America as an ideal has also been acid-dripped by the academy), but also for order, civility, protection, and romantic love . . .

Is it sixty years or as in his earlier quote, forty years? What exactly happened in “academia” and why and who did it? There are plenty of answers on offer here at Counter-Currents.

But hey, it’s a short book, and Bell deserves all the praise and credit deserved by someone who at least senses something’s wrong and — unlike so many with their “answers” — actually tries to do something practical about it.

If you’ve read Bell’s thrillers, or his books on how to write fiction [17],[12] [18] you’ll recognize his style here. He’s closer to Spillane than Chandler; narrative looks as much like dialogue as possible, plenty of one sentence paragraphs with lots of white space on the right side.

And that’s okay with me.

It’s a good, hard-punching style that fits the material.

Like a glove.

A boxing glove.

This is good stuff, and well worth your attention if, as Bell says, you are a young man looking for guidance, a father looking for ways to get the message across, a mother who has to do the same thing in the absence of a suitable male figure, or even a woman looking for the right man and wondering what to look for.

He’s right there, lady, right there in the cable listings.

Notes

[1] [19] No, not Father Brown, you beast!

[2] [20] The locus classicus here, of course, is that bloody socialist Orwell’s “Raffles and Miss Blandish,” which Wikipedia says was “first published in Horizon in October 1944 as ‘The Ethics of the Detective Story from Raffles to Miss Blandish.'” “In America, both in life and fiction, the tendency to tolerate crime, even to admire the criminal so long as he is successful, is very much more marked.” We’ll see how accurate that is as we examine the book under review.

[3] [21] The Importance of James Bond & Other Essays [22], edited by Greg Johnson (San Francisco: Counter-Currents, 2017); reviewed here [23].

[4] [24] “Humphrey Bogart: Man Among the Cockroaches,” reprinted in The Homo & the Negro: Masculinist Meditations on Politics and Popular Culture [25]; edited by Greg Johnson (Second, Embiggened Edition; San Francisco: Counter-Currents, 2017); “Welcome to the Club: The Rise and Fall of the Männerbund in Pre-War American Pop Culture,” reprinted in Green Nazis in Space! New Essays on Literature, Art, & Culture [26]; edited by Greg Johnson (San Francisco: Counter-Currents, 2015); and perhaps “St. Steven of Le Mans: The Man Who Just Didn’t Care,” here [27].

[5] [28] Bell notes that the French, such as Jean Luc-Goddard, regard Angel Face (1953) as “among the best films of all time.” We’ll come back to it, and its director, Otto Preminger.

[6] [29] Spencer Tracy? Noel Coward? Alfred Lunt? Lynn Fontanne? Anonymous? See the Quote Investigator, here [30].

[7] [31] As we’ll see, Bell doesn’t have much interest in what caused this change in manly behavior; for a controversial theory that might explain the loss of charm, see James J. O’Meara, The Homo & The Negro, especially the title essay and, as applied to the Wild West, “Wild Boys and Hard Men.”

[8] [32] Referring to “metrosexual,” of course, not the beastly London suburbs grandpa mildly deplored, although Harriet Walter was both Lady Metroland in Bright Young Things (2003) and granddad’s future wife in the BBC dramatization of his adventure Strong Poison (1987).

[9] [33] It’s interesting that while “metro, not manly” has become acceptable, today’s audiences no longer accept “old-time” ideas of masculine fitness. As James O’Meara noted, Family Guy mocks Robert Mitchum as an “out-of-shape in-shape ’50s guy” while Mystery Science Theater chuckles at actors who “look like a nineteenth-century ‘strong man’.” See his discussion of these paradoxes in “The Ponderous Weight of the Dark Knight,” reprinted in Dark Right: Batman Viewed from the Right [34], ed. Greg Johnson and Gregory Hood (San Francisco: Counter-Currents, 2018). Personally, I would not try to tangle with Mitchum. On the other hand, Bell’s claim that “Even men who have a naturally wiry frame can develop strong, ropey muscles. (For a movie example, watch the Westerns Jimmy Stewart made in the 1950s. Stewart successfully transitioned from his early ‘Aw shucks’ image into a tough-as-nails Western hero)” recalls another MST3k comment on a notably pasty and scrawny character: “Must’ve bought the James Stewart workout tape.”(Episode 1005, Blood Waters of Dr. Z [35], at 15:58). For more on Jimmy Stewart’s lessons in manliness, see here [36]. Not to be confused with actor James Stewart, who does indeed have his own workout plan [37].

[10] [38] “The Dry Martini is the most famous and the best cocktail in the world. . . . The basic ingredients are gin and dry vermouth. Any nationally known gin is suitable, but the vermouth must be Martini Rossi dry — the name is a coincidence, nothing to do with the name of the cocktail. The standard recipe tells you to pour four measures of gin and one measure of vermouth into a jug half full of ice, stir vigorously for at least half a minute, strain, and serve in small, stemmed glasses.

“There are variations on this. Some authorities, including James Bond, recommend shaking rather than stirring the mixture, which looks good but which I regard as a bit flashy. Rockefeller and his chums probably drank equal parts of gin and vermouth. Since then, people have come to prefer their Martinis drier and drier, i.e. with less and less vermouth. Sixteen parts gin to one vermouth is nowadays considered quite normal. Anyway, that’s about how I like it. Finding out by experiment the precise balance you favour is no great ordeal. Don’t hurry it.

“Such is the classical or ‘straight-up’ Dry Martini, with ice used in the mixing jug but no ice in the glass. The problem is that it starts to lose its chill from the moment of serving. Far more than any other drink, it deteriorates as it warms up. Stirring with ice in the jug as before and then serving on the rocks is the solution, and quite trendy enough. Realize that it means fresh ice cubes not only for first drinks but for all subsequent ones too, that’s if you want to do things properly.

“I always try a Martini out of curiosity if offered one at a private house. I would never ask for one in a pub, as opposed to a cocktail bar. Even if I got across that I didn’t want a glass of plain vermouth (horrible muck on its own), I would be bound to be given a drink with too much vermouth in it. In an emergency I’d consider calling for a large gin and a small vermouth, dipping my finger in the vermouth and stirring the gin with it.

“The best Dry Martini known to man is the one I make myself for myself. In the cold part of the refrigerator I have a bottle of gin and small wineglass half full of water that has been allowed to freeze. When the hour strikes I half fill the remaining space with gin, flick in a few drops of vermouth and add a couple of cocktail onions, the small, hard kind. Now that is a drink.

“There was a man in New York one time who bet he could drink fifteen double Martinis in one hour. He got there all right and collected his money but within anther minute he fell dead off his bar stool. Knock that back and have another.” Kingsley Amis, Everyday Drinking: The Distilled Kingsley Amis (London: Bloomsbury, 2008).

[11] [39] Bond agrees with the “one drink” rule, but with several provisos; the famous Vesper Martini recipe – served in a deep champagne goblet — begins thus: “I never have more than one drink before dinner. But I do like that one to be large and very strong and very cold and very well-made. I hate small portions of anything, particularly when they taste bad.” —Ian Fleming, Casino Royale, Chapter 7, “Rouge et Noir.”

[12] [40] Especially How to Write Pulp Fiction (Woodland Hills, Cal.: Compendium Press, 2017).