The Aryan Ethos:

Loyalty to One’s Own Nature

Posted By

Julius Evola

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

Today, more than ever, one must understand that social problems, in their essence, are rooted in problems of ethics and world-view. Anyone who thinks that social problems can be solved through purely technical means, is like a doctor who only wants to treat the patent symptoms of a disease, rather than examining and treating its deep causes. The greater part of the crises, disorders, and unresolved tensions that characterize modern Western society depend not simply on material factors, but, to at least an equal degree, on the surreptitious substitution of one world-view by another. This new attitude towards oneself and towards one’s own destiny has been celebrated as a triumph, when in fact it represents a deviation and a degeneration.

Particularly relevant to the issues that will be discussed here is the opposition between the modern “activistic,” individualist ethic and the traditional and Aryan doctrine concerning “one’s own nature.”

In all traditional civilizations — all those that the empty arrogance of historicism dismisses as “antiquated” and the Masonic ideology deems to be “obscurantist” — the principle of a fundamental equality of human nature was always an alien notion, and considered an obvious aberration. Every being has, from birth, its own “nature,” which is to say, its own face, its own quality, its own personality, albeit more or less differentiated. According to the oldest Aryan and classical teachings, this was not viewed as the result of chance, but as an intimation of a kind of decision or determination prior to the human condition of existence itself. In any case, this fact of having “one’s own nature” was never viewed as a destiny. One is unquestionably born with certain tendencies, certain vocations and inclinations, sometimes patent and clearly defined, sometimes latent and only manifesting themselves under particular circumstances or when subjected to certain tests. But everyone has a margin of freedom with respect to this innate, differentiated element, which is linked to birth, if not — as expressed by the teachings mentioned previously — to something coming from far away, preceding birth itself.

This is where the opposition between two paths and ethical attitudes manifests itself: between the traditional and the “modern.” The cornerstone of the traditional ethos is to be oneself and to remain loyal [true] to oneself. One must know what one “is,” and will it, rather than attempt self-realization in a form that is different from what one is.

This in no way implies passivity or quietism. Being oneself is always, to some degree, a task, a “standing firm.” It implies a strength, an uprightness, a development. But here, this strength, uprightness and development are grounded in, and an extension of, innate dispositions. They are linked to character, and manifest themselves in traits of harmony, self-coherence and organic wholeness. In other words, man orients his existence towards being “all of one piece.” His energies are directed towards potentiating and refining his nature and his character and defending it against every alien tendency, against every altering influence.

It was thus that ancient wisdom formulated maxims such as these: “If men impose upon themselves a norm of action that is not in conformity with their nature, this must not be considered a norm of action.” And further: “One’s own duty, even if imperfectly performed, is better than doing the duty of another perfectly. To die while performing one’s own duty is preferable; doing the duty of another carries great dangers with it.” This loyalty to one’s own way of being even took on a religious value: “Man realizes perfection,” an ancient Aryan text [the Bhagavad Gita] states, “when he worships him from which all living things proceed and who pervades all beings, by fully actualizing his own way of being.” And also: “Always do what must be done (in accordance with your own nature), without attachment, because he who acts with an active disinterestedness accomplishes the Supreme.”

Unfortunately, it has become common, today, to be horrified by any mention of the caste system. “Castes”?! Today people no longer even talk of “classes,” and barely of “social categories.” Today, “stagnating divisions” are overcome, and the “people” is embraced.

The prejudice against the caste system is due to ignorance, and can in the best of cases be explained by the fact that, rather than considering the principles upon which a system is based, one dwells upon its deviant, empty or degenerating forms. First of all, it should be noted that “caste” in the traditional sense has absolutely nothing to do with “class,” the latter being an artificial division on an essentially materialistic basis, while caste is linked to the theory of an authentic nature and the ethos of loyalty to one’s own nature. For this reason — furthermore — there often existed a natural, de facto caste system, without any need for a positive institutionalization, and hence without the term caste or a similar word even being used; this was, to a certain extent, the case in the Middle Ages.

In recognizing his own nature, traditional man also recognized his “place,” his proper function, and just relations of superiority and inferiority. In principle, the castes, or equivalents of castes, prior to defining social groups, defined functions, typical ways of being and acting. The fact of the correspondence between, on the one hand, the individual’s own nature — innate tendencies which subsequently are affirmed — and on the other hand, a function, determined the fact of his belonging to a corresponding caste, in such a way that he could recognize in the duties of his caste the normal unfolding and development of his own nature.

Thus, in the traditional world, the caste system often appeared as a calm, natural institution, founded not on exclusion, arbitrariness or the abuse of power by a minority, but on something that was self-evident to everyone. Fundamentally, the well-known Roman principle of suum cuique tribuere is based on the same idea: to each his own. Since beings are unequal, it is absurd to demand that everyone have access to everything, and to claim that anyone, in principle, is qualified to perform any and every function. That would mean a deformation, a denaturing.

The difficulties that arise in the minds of those who look at the current conditions, quite different from the system being discussed, come from imagining cases in which the individual manifests a vocation and talents different from those appropriate to the group in which he finds himself by birth and tradition. However, in a normal world, such cases have always been exceptions, for a precise reason: because in those times, the values of blood, race and family were naturally recognized, and in this way, a biological, hereditary continuity of vocation, qualifications and traditions was maintained. This is the counterpart of the ethic of being oneself: minimizing the possibility of birth actually being a matter of chance, and hence of the individual being rootless, in disharmony with his environment, with his family and even with himself, with his own body and his own race. Moreover, it must be emphasized that in the aforementioned civilizations and societies, materialistic and utilitarian factors were to a large extent subordinated to higher values, which were inwardly experienced. Nothing seemed more worthy than following one’s own tradition, than performing one’s natural activity, than following the vocation truly appropriate to one’s own mode of being, however humble or modest it might be: so much so, that it was even conceivable that he who keeps within his station in life and performs its duties with purity and impersonality, has the same dignity as a member of any of the “higher” castes: an artisan could be the equal of a member of the warrior aristocracy or a prince.

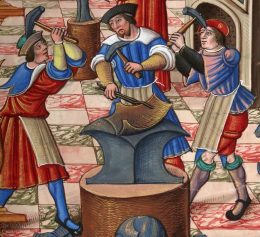

It was from this that developed the sense of dignity, quality, and conscientiousness that manifested itself in all traditional professions and organisations; the style, by virtue of which a blacksmith, carpenter or shoemaker did not appear as men degraded by their condition, but almost as “lords,” as persons who had freely chosen and exercised their activities, with love, always giving it a personal and qualitative stamp, keeping themselves aloof from the unmitigated concern for gain and profit.

The modern world, however, has by and large traveled the opposite path, the path of the systematic neglect of one’s own nature, the path of individualism, of restlessness and social climbing. Here, the ideal is no longer to be what one is, but to “construct” oneself, to involve oneself in all kinds of activities, randomly, or for completely utilitarian reasons; no longer to actuate one’s own being with serious consistency, loyalty and purity, but to use all of one’s strength to become what one is not. While individualism — the atomized, nameless, raceless, and traditionless man — is the foundation of this way of looking at things, its logical consequence has been the demand for equality, i.e., the claiming of the right to be able to be, in principle, everything that anyone else might be, while refusing to recognize any differences as more true and just than those artificially created by oneself, in terms of this or that form of a materialized and secularized civilization.

As is well-known, this form of deviancy has reached its extreme form in the Anglo-Saxon and puritan nations. Along with them, the masonic Enlightenment, democracy, and liberalism have formed a common front. Things have reached the point where many see innate and natural differences as being brute contingent facts, where every traditional point of view is seen as obscurantist and anachronistic, and one does not sense the absurdity of the idea that everything should be open to everyone, that everyone has equal rights and equal duties, that there is only one morality, which should be imposed in the same measure on everyone, in complete indifference towards different natures and different inner dignities. This is also the basis of every form of anti-racism, the denial of the values of blood and the traditional family. Thus, one can rightly speak here, without undue delicacies, of a real “civilization” of the “casteless,” of pariahs, who pride themselves in being such.

It is precisely within the framework of such a pseudo-civilization that classes come into being. Class has nothing to do with caste, it has no organic and traditional basis, but is instead an artificial social grouping, determined by extrinsic factors which are almost always of a materialistic nature. Class almost always arises on an individualistic basis, in the sense that it is the “place” that brings together all those who, through their enterprise, have climbed to the same social position, in complete independence of what they by nature truly are. These artificial groupings then tend to crystallize, thereby generating the tensions known to all. In fact, the disintegration characteristic of this type of “civilization” accomplishes the degradation of the “arts” to mere “work,” the transformation of the of the old artificer or artisan into the proletarianized “worker,” whose activity is reduced to being only a means of earning money, and who is only capable of thinking of “salaries” and “working hours.” Little by little, artificial needs, ambitions, and resentments are aroused in him, since in the end the “upper classes” no longer display any quality that might justify their superiority and their possession of a larger quantity of material goods. Thus, class struggle is one of the ultimate consequences of a society that has been denatured, and considers this denaturing, the neglect of one’s own nature and of tradition, to be a triumph and a form of progress.

Here, too, a racial background can be taken into consideration. The individualist ethic undoubtedly corresponds to a condition of the mixing of peoples and stocks, to the same extent that the ethos of being oneself corresponds to a state of prevalent racial purity. Where races are mixed, vocations become confused, it becomes more and more difficult to see clearly into one’s own being, and inner instability, which is a sign of a lack of true roots, increases. Race-mixing promotes the emergence and reinforcement of the consciousness of man as “individual,” and it also favors activities that are “free,” “creative” in the anarchic sense, shrewd “skill” and “intelligence” in the rationalistic and sterile, critical sense: all of this at the expense of the qualities of character, the dimming of the sense of dignity, of honor, of truth, of uprightness, of loyalty. Thus, a spiritually tortuous and chaotic situation is established, which, however, seems normal to many of our contemporaries. The cases of individuals full of contradictions, whose lives lack any meaning, who no longer know what they want beyond material things, who are at odds with their own tradition, their own birth and their natural destination, no longer appear to them as anomalies or monstrosities, but as part of the natural order of things, which then supposedly proves that every limit set by tradition, race and birth is artificial, absurd and oppressive.

This fundamental opposition of ethics and general vision of life, should, to a greater degree than has heretofore been the case, be taken into consideration by those who are concerned with social problems and talk of “social justice,” if they are actually to overcome the evils that they struggle with in good faith. There can be no rectifying principle, except where the absurd classist idea has been transcended by means of a return to the ethos of loyalty to one’s own nature, and hence to a well-differentiated and articulated social system. We have often said that Marxism, in many cases, did not appear because of a real “proletarian” destitution, but the other way around: it was Marxism that created a denatured proletarianized working class, full of resentment and unnatural ambitions. The most exterior forms of the evil that must be combated can be treated by means “social justice” in the sense of a more equal distribution of material goods; but its inner root will never be destroyed, without energetic action on the level of general world-view; without reawakening the love for quality, personality, for one’s own nature; without restoring the prestige of the principle, denied only in modern times, of a just difference, in conformity with reality, and if the right conclusions are not drawn from this principle on all levels, albeit with special consideration of the type of civilization that has become prevalent in the modern world.

Source: La Vita Italiana, March 1943