Now in Audio Version

Identity & the Problem with Christianity

Posted By

C. B. Robertson

On

In

Counter-Currents Radio,North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

2,843 words / 19:06

To listen in a player, click here [2]. To download the mp3, right-click here [2] and choose “save link as” or “save target as.” To subscribe to the CC podcast RSS feed, click here [3].

Race is a large component of identity that has been neglected in recent decades, so naturally, identitarians ought to care about race. Identity is valuable because it gives coherence to our relationships with our ancestors and descendants, it builds social trust and solidarity in our communities, and it helps establish who we are as individuals. Without such an understanding or awareness of who we are, any greater purpose or justification for life can be difficult to ascertain.

Whenever we accept certain axioms as true, we bar ourselves from accepting certain conclusions which contradict the axioms. For example, if we accept the axioms that identity matters, and that race is a component of identity, then one cannot claim that race does not matter.

But race is not the only component of identity. Indeed, in many circumstances and situations, it may not even be the most critical component of identity. Religion often competes with race for predominance, and the axioms of identity and the barring of certain conclusions apply to religion in the same manner that they apply to race.

What I am about to say may seem divisive in an already weak movement, and as such, inappropriate as a subject. But there is an old tale about the importance of building one’s house upon solid rock, rather than on sand, because no matter how well-built the house may be, a weak foundation will bring it all crashing down when the winds begin to blow. Religion being a critical component to the foundations of identity, it should be taken seriously because smaller differences than religion have fractured nations when allowed to fester.

First let me give a little bit of relevant personal background. I have spent the last two and a half years attempting, to the best of my ability, to be a Christian. I grew up Christian and was reasonably well-read. Like many teenagers, I was heavily influenced by the New Atheists, particularly Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins, and left the faith in my sophomore year of High School, gradually maturing into the most insufferable variety of atheist.

After discovering Joseph Campbell several years later, my tune began to change. Maybe I had been thinking about religion all wrong this whole time?

My first inclination, incidentally, was not Christianity but paganism. I had been learning and adapting myself more and more to pagan beliefs, until it occurred to me that within both Christian and Pagan worldviews, social relationships are not merely important, but are in many ways the heart of spirituality. My family was Christian; my wife was Christian; my in-laws were culturally Christian; my extended family were all Christian or culturally Christian. Wouldn’t it be a selfish abandonment of my family to become pagan? Wouldn’t it be arrogant of me to assume that I knew something they did not, and to separate myself religiously from them?

And so I adopted Christianity: for my family, informed by mythological parable, and grounded in faith. This to me seemed like an adequate justification to choose Christianity, or to seriously choose any other religion for that matter [4].

As it turns out, this line of reasoning is compatible with paganism, but is incompatible with Christianity:

Now therefore fear the Lord, and serve him in sincerity and in truth: and put away the gods which your fathers served on the other side of the flood, and in Egypt; and serve ye the Lord.

And if it seem evil unto you to serve the Lord, choose you this day whom ye will serve; whether the gods which your fathers served that were on the other side of the flood, or the gods of the Amorites, in whose land ye dwell: but as for me and my house, we will serve the Lord.

—Joshua 24:14-15

In the Old Testament, and the New:

If any man come to me, and hate not his father, and mother, and wife, and children, and brethren, and sisters, yea, and his own life also, he cannot be my disciple.

—Luke 14:26

Holding to Christianity because it is the religion of your fathers is, according to scripture, the incorrect reason.

Needless to say, I had a hard time with the literal truth of the doctrine, but what of the metaphorical value? What if Adam was an archetypal representation of the evil in man that we all recognized, and Christ’s redemption of man was, in his humanity, an act so good—and through it, proof that man was capable of such an act—that by itself, his death on the cross gave us reason to hope in others, here on this earth? And isn’t the Kingdom of God within us?

As with the religion of the father, this logic actually does apply to paganism [5], but fails with Christianity, no matter what Campbell or his modern avatar, Jordan Peterson, might say. Even Bishop Robert Barron, who presents a great defense of the classical conception of God [6] more sophisticated than what the New Atheists generally attack, has a critical word to say about their gnostisizing tendency [7], to “bracket historicity, to uncover a sort of secret or hidden wisdom in these texts.” The danger, according to Barron, is missing the immense importance of whether or not certain things happened. Ultimately, Christianity does not, and cannot, boil down to psycho-narrative interpretations of world forces. It hinges upon Jesus, the person, actually dying on an actual cross, and actually, literally, rising from the dead three days later. If this did not happen, or if we are not given the chance of immortality as a result of its happening, then according to the Church fathers themselves, Christianity is wrong.

And if Christ be not risen, then is our preaching vain, and your faith is also vain.

—1 Corinthians 15:14

What about faith?

Faith is the last, and the strongest justification. Casually dismissed as “wishful thinking” by Hitchens, it is the great Kierkegaardian leap that allows us to act even in the face of uncertainty. But what should we have faith in? The case for Christian faith lies, to a great degree, in the attractiveness of its story and its metaphysical conception of the universe. The reason to have faith in Christianity—as opposed to faith in another religion—is because the story is comforting, encouraging, and life-giving. All “informed by reason” too, of course.

Here is where the conflict between Christianity and identitarianism comes becomes important.

First of all, I don’t mean identitarianism in the petty, political sense. Politics is always a means to an end, and if politics were conflicting with spiritual matters, it is obvious we ought to choose the latter. But identity itself is a spiritual matter, and the conflict cuts to the heart of what it means to be an individual in the modern world.

First, Christians accept that all people are “image-bearers” of God, and are intrinsically worthy of respect as not only creations of God, but in many ways as proxies for God himself:

And the King shall answer and say unto them, Verily I say unto you, Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.

Then shall he say also unto them on the left hand, Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels:

For I was an hungred, and ye gave me no meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me no drink:

I was a stranger, and ye took me not in: naked, and ye clothed me not: sick, and in prison, and ye visited me not.

Then shall they also answer him, saying, Lord, when saw we thee an hungred, or athirst, or a stranger, or naked, or sick, or in prison, and did not minister unto thee?

Then shall he answer them, saying, Verily I say unto you, Inasmuch as ye did it not to one of the least of these, ye did it not to me.

—Matthew 25:40-45

Christianity in this way holds us to be our brother’s keeper. But our brother is not merely our biological brother; in Christ, all believers are family, are one:

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.

—Galatians 3:28

This famous Galatians verse does not, incidentally, deny basic national and biological differences between people, but rather establishes an ethical obligation between the body of believers that is familial. This familial bond is often even extended to unbelievers by particularly zealous Christians, who trust the welfare of their families, their nations, and themselves to foreigners and strangers who do not share their faith. This is not theologically sound, so far as I can tell, but it is illustrative in its visible instincts of how Christians are expected to treat other Christians. Those who have faith in Christ are brothers in Christ [8].

This creates a number of problems relating to identity.

First, our identities as individuals are not revealed by removing or blurring connections with others but are forged through connection with others. These other people cannot be just anybody, as the first set of connections is one that we are born into: namely, the genetic connection with our parents and our ancestors. Biological brothers and sisters fall within this familial category as well. They are our real family. Christianity, by first requiring us to leave our family in order to follow Christ, and second by expanding our “family” to extraordinary, inhuman proportions, diminishes our ability to establish a coherent self that is reliable to others, because it denies the inherent validity and importance of the core relationships that ground us and shape us into beings that can connect with our parents. The only route of authentic re-connection for the parent to the Christian child is through Christianity; the fact that these parents created you and raised you from infancy is not sufficient, because we are told that our parents did not really create you. God did that.

It should be said that there is a real intimacy in Christian relationships, which I do not mean to dismiss. But it is a distinct and separate kind of relationship, one which is shoulder-to-shoulder, rather than face-to-face. Both parties face together towards God, and learn about each other by learning about God, to the degree that each continues in their faith and emulation of Jesus.

But God is not merely the object of attention. He is also the eternal observer and the final adjudicator. We are never completely alone with someone else, nor, in the final analysis, does God permit the resolution of disputes between individuals to be handled by these individuals. While Matthew 18:15-17 pays lip-service to the procedure of resolving disputes amongst individuals, it is only lip-service because within the Christian framework, it is not other people whom we wrong, but God. The fact is that other people are, as people, only proxies for God, deserving of respect precisely—and solely—because they are image-bearers of God (God being the only proper object of worship). When we wrong other people, the victim is not the actual person wronged, but God. Even if the Christian acknowledges that there is something intrinsically wrong with harming another person regardless of God (many of their moral arguments hinge upon this point being false), the wrong against the individual is so petty, in scope, in injustice, and in consequences, compared to the wrong done to God that it is relatively meaningless.

Human relationships aren’t fundamentally built upon getting along with each other. That’s a necessary condition, most of the time, but if you simply agree with someone on absolutely everything, you will not develop the deepest kinds of human bonds. Those are acquired through having and resolving conflicts. By relocating the conflict from between two individuals and making it between the individual and God, we deny ourselves the opportunity to develop deep relationships with others and are redirected instead to deepening our relationship with God.

This redirection threatens intimacy—at least the face-to-face variety—but it also threatens the classical notion of honor, which requires us to stick up for ourselves and to care about our reputation. Within the Christian worldview, vengeance belongs to the Lord. It is God’s task—not yours—to take care of yourself and your reputation.

All of this culminates in a kind of spirituality that is rightly credited as the antecedent to modern conceptions of individualism, wherein human identity is truly discovered by removing ourselves from all ties to the earth, rather than identifying what those ties are and refining them.

The modern world presents us with a serious problem. The unholy scale of human migration we are experiencing has not been seen ever before in human history. Historically, genocides, the collapses of empires, the forging of new peoples and the destruction of old nations usually followed such movements, and survival in such turbulent seas requires a heavy anchor and a strong rope. It requires a clear sense of identity, so that when that identity comes under attack, the attack can be identified and defended against.

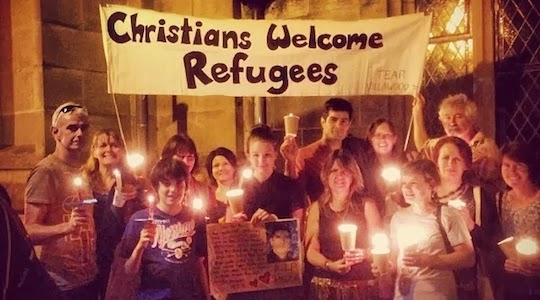

What does Christianity have to say about this? It requires one to be at worst, ambivalent. Life on this earth is ultimately of no importance, after all. On the other hand, many view the movement and migration as a good thing. Why? Not merely from fear and trepidation around open-borders progressives. Just last week, I was at an evangelism conference, and the speaker was saying how wonderful it was that all of these refugees were coming in because we could all proselytize to unbelievers without having to cross an ocean. They were coming to us! How wonderful!

Even caring about the demographic dangers, let alone bringing them up, violated Galatians 3:28. Don’t you know that these immigrants are your brothers too? And don’t you know that you are your brother’s keeper?

Within Christianity, there is neither mother nor father, daughter nor son, stranger nor friend; for all are one in Christ. There is no cohesive identity in Christianity, no identifiable self or lineage to get upset about should it be put in danger of annihilation. The Lord giveth, and the Lord taketh away. The indifference to life, to family, and to nation (relative to God) that Christianity requires makes it a path of death in the modern age.

I understand that the historically-minded Christians may point back to a history of great civilization under Christendom and ask how these conclusions could possibly be justified in the face of the facts. Indeed, the West has achieved great things under the Christian flag, but the attribution of this success to Christianity is not merely questionable, but theologically unsound, placing value on worldly accomplishments rather than upon godliness of the spirit. This was a point which Augustine makes in City of God, when confronting Pagans who blamed the rise of Christianity for the collapse and sacking of Rome:

If those who lost their earthly riches in that disaster had possessed them in the spirit thus described to them by one who was outwardly poor but inwardly rich; that is, if they had ‘used the world as though not using it,’ then they would have been able to say, with that man who was so sorely tried and yet was never overcome: ‘I issued from my mother’s womb in nakedness, and in nakedness I shall return to the Earth. The Lord has given, the Lord has taken away. It has happened as God decided. May the Lord’s name be blessed.’ Thus a good servant would regard the will of God as his great resource, and he would be enriched in his mind by close attendance on God’s will; nor would he grieve if deprived in life of those possessions which he would soon have to leave behind at his death.

—Augustine of Hippo, City of God

Even if most believers don’t understand or accept the true ferocity of this dedication, their allegiance to the faith will eventually leave them morally powerless to oppose those who do sincerely adopt the principles of Christian identity unadorned with un-Christian idols, like “survival.” I think we are reaching this point of conflict, which does not require us to run like cowards from our spiritual loyalties, but rather reveals that the Christian God is not in fact the God of the living [10], but the God of the dead and soon-to-be dead.

The astute Christian reader will recognize that this whole argument has no power whatsoever if the religion is, in fact, true. But for those who are uncertain or uninterested in the truth, but are coming to the realization that spirituality matters, and consider Christianity to be a viable candidate for their own mytho-poetic spiritual exploration, you should understand that Christianity is incompatible with any form of identity other than that of being a Christian. The Christian God is a jealous God, and there is no room for serving multiple masters. There is but one God, and nothing—nothing—else matters.