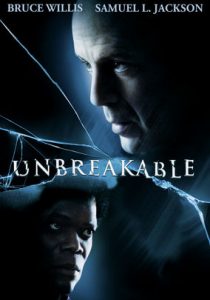

Unbreakable

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledUnbreakable (2000) is many people’s least favorite M. Night Shyamalan film, but I think it is his best: brilliantly conceived and scripted, beautifully acted and filmed, and quite moving. Since the film is almost two decades old, I trust nobody will complain about spoilers.

Unbreakable is a superhero film, but it does not contain any computer animation, strobe-fast editing, or deafening crashes and booms. Instead, Unbreakable has the pacing and style of an art film. It is highly realistic, but in a glossy rather than gritty fashion. Shyamalan’s camera imbues mundane objects and scenes with a luster that blunts any desire to look beyond their surfaces. His goal — which is communicated even in his use of low camera angles — is to conjure up a world in which the fantastic and heroic exist only in the imagination.

As Elijah Price — Samuel L. Jackson in one of his most emotionally powerful roles — says, this is “a mediocre time.” “People are starting to lose hope. It’s hard for many to believe that extraordinary things live inside themselves as well as others.” The “surprise ending” of the film is the discovery that extraordinary possibilities really do exist in the comfortably superficial world Shyamalan’s camera has created.

Unbreakable may be a superhero film, but the key to its emotional power is that it is an allegory about the fate of everyman—literally every man, and manliness itself—in an overly feminized and bourgeois society that prizes the long and inglorious life over the riskier, more glorious path.

The hero of Unbreakable is David Dunn, played by Bruce Willis. Dunn is a bald, middle-aged, unassuming everyman. He works as a security guard, while his wife Audrey (Robin Gayle Wright) is a physical therapist. The Dunns have one child, their eleven-year-old son Joseph. Of course, “Dunn” has the connotation of dull, and Audrey’s maiden name “Inverso” is an omen of their relationship, since she is the dominant partner in the marriage. She has a profession, whereas David is blue-collar. David also defers to Audrey in all matters connected with their son, including discipline. Joseph wants to look up to his father and spend time with him doing man things, like playing football and working out, but Audrey thinks they are unsafe. Unsurprisingly, the Dunns are both unhappy in their marriage. They sleep in separate beds while they plan their separation and divorce.

Every morning, David Dunn awakens to a feeling of sadness. Later we learn why. In college, David Dunn was not a soft-spoken schlub. He was the star quarterback on his football team, winning games and adulation, perhaps in the very stadium where he is now merely a security guard. David and Audrey were dating in college, and they were in a terrible car accident. David quit playing football after the accident, claiming injury. But it turns out that was just an excuse. Although David had been thrown clear of the car, he was not injured at all, and he had the strength to save Audrey from the burning wreckage.

The real reason David quit playing was Audrey’s moral opposition to football. As an aspiring physical therapist, her purpose was to fix broken bodies, whereas football broke bodies in the pursuit of glory. Thus Audrey domesticated David, getting him to quit football. They both thought it would make them happy, but it didn’t. Domesticity is emasculating. Men can’t be happy without taking risks, and women aren’t really attracted to emasculated men. Modern bourgeois society programs couples to make marriages equal and risk free, even though that is not really what people want, and getting it doesn’t satisfy them.

At the beginning of the movie, David is returning home to Philadelphia from a job interview in New York. His train derails and is struck by a freight train. Everyone is killed except for David, who is not even scratched. After a memorial service for the victims, David finds a note on his windshield asking him if he has ever been ill. The card reads Limited Edition, the name of a comic book art gallery owned by Elijah Price.

Elijah is the only child of an unwed black mother in a Philadelphia slum. He was born with a rare genetic disease, osteogenesis imperfecta, which makes his bones highly brittle. Because of this he spent most of his life indoors, avoiding injury, when not actually in hospital beds. Elijah is highly “breakable.” The children in his neighborhood mocked him as “Mr. Glass.”

Elijah spent a great deal of his life reading comic books, and when he grew up, he turned his expertise into a business. Elijah is convinced that comics communicate truth in symbolic form. Specifically, he thinks that superheroes and supervillains may actually be real. Thus when he heard that David had survived the train crash “miraculously unharmed,” he reached out to him, thinking that he might be an extraordinary person, chosen for a special destiny.

Elijah’s quest is sustained by a metaphysical conviction: “If there is someone like me in the world, and I’m at one end of the spectrum . . . Couldn’t there be someone the opposite of me, at the other end?” Elijah is quite certain this is the case. This conviction is known as the “principle of plenitude,” which holds that all possibilities are actual, or will be actualized in the fullness of time. If Elijah is Mr. Glass, Mr. Breakable, doesn’t that mean there is a Mr. Unbreakable somewhere in the universe? If such a person exists, then Elijah wants to find him. If he does not know his own powers, Elijah wants to help him discover them.

Elijah has at least two motives for his search. First, he thinks the world is in need of heroes to free it from flatness and mediocrity and give it meaning. Second, Elijah believes that discovering his counterpart would give his own life meaning. It would allow him to make something good of his suffering and alienation.

This brings us to a second classical philosophical principle: the actualization of potentiality. For humans, becoming who we really are is the path to well-being or happiness. Each human being has an ideal self, which needs to be actualized. If we actualize ourselves, we feel happy. If we fail to actualize ourselves, we suffer. But whether we flourish or fail, we are the same persons in either case.

David Dunn is unhappy, because he has failed to actualize himself. He fails because he does not know himself, and he does not know himself because his wife convinced him not to test his limits. Unbreakable is a moving film, because self-discovery and self-actualization are necessary for the well-being of every one of us. David, urged on by Elijah and his son Joseph, discovers that he has extraordinary powers: He can intuit crimes by touching people. He is enormously strong. And he is almost invulnerable. Water is his only weakness. It is his kryptonite.

As David begins to understand and actualize his powers, he shakes off the sadness that has haunted his life and ruined his family. He bonds with his son but also feels comfortable disciplining him authoritatively. After his first major rescue, when he saves two children from a home invader who has killed their parents, he carries his wife upstairs to his bed. It is a primal, paleo-masculine gesture, and Audrey loves it. The next morning, the family is united around the breakfast table, and Audrey is cooking for them.

Unbreakable does not merely celebrate paleomasculinity but also specifically white athleticism—contrasted with black fragility. In one scene, we are introduced to a Temple University cornerback who is mentioned early on as being destined to go professional. Every other director would cast a black. But instead, Shyamalan casts a magnificent blond, idolized by white schoolboys who leap up to hang off his flexed biceps. Shyamalan handles it without a touch of irony.

David goes to visit Elijah and tells him what has happened. Elijah asks him if the sadness is still there, and David answers “No.” Then Elijah says, “I think this is where we shake hands.” When David takes Elijah’s hand, he intuits what Elijah has done. Elijah has caused an airplane to crash, burned down a hotel, and derailed David’s train, killing hundreds of people in the process—all in search of a man who could survive miraculously unharmed. Elijah always wondered why he suffered. What his place and purpose were in this world. Finding David gave him an answer. It gives new depth to one of the Joker’s lines to Batman in The Dark Knight: “You complete me.” It is terrifying but logical. Surprising but necessary. For if David is Elijah’s opposite, that makes Elijah a supervillain. If Elijah’s body was so breakable, then of course his mind and character were breakable as well.

But the kids knew it all along. They called him Mr. Glass.

It is an unforgettable scene, brilliantly played by Jackson, whose powerfully expressive voice makes him compelling despite his grotesque appearance and evil deeds. David Dunn walks out of the store, and a caption informs us that he led police to evidence of three acts of terrorism, for which Elijah Price was confined to an institution for the criminally insane.

I loved this ending. You realize with a start that you have just been drawn into a classic “origin story.” But because of Shyamalan’s art-film style, it sneaks up on you. Once you get to the end, of course, you realize there were signs all around you. For instance, Elijah dresses in a quasi-Empire style, carries a cane made of glass, drives a vintage car whose interior is padded with black foam eggs, and runs a high-end art gallery. Aside from black, his colors are purples and dark blues. In his wheelchair, he looks like a cross between Stephen Hawking and Prince. But I never thought Elijah was actually a comic book supervillain. I just thought that he had spent a bit too much time reading about them. James Newton Howard’s understated Holst-like score also intimates genuine heroism and magic without going full Star Wars.

The end of Unbreakable of course sets you up for a sequel. You want a sequel, because Elijah Price is a psychologically interesting villain. He is obviously not maliciously or sadistically evil. He does not kill because he thinks it is bad. He kills because he believes it is good, that it is necessary to find his counterpart. And once he finds him, helps him discover who he is, and sets him on the path to heroism, he feels it is time to confess his crimes. For the sole purpose of Elijah’s supervillainy is to be the midwife to the birth of a superhero, a hero who will eventually save far more people than were sacrificed to bring about his birth.

One wonders what would happen to such a generous but twisted soul if left to stew long enough in the inevitable bitterness of being confined to the equivalent of Arkham Asylum while David Dunn is out saving people.

But I was certain that Unbreakable was just a one-off stunt, and even if Shymalan had considered a sequel, he would have been deterred by the film’s generally unfavorable reception. Much to my delight, however, as I searched for an online version of the Unbreakable script, I learned that in 2019, Shyamalan, Willis, and Jackson will return to the big screen with Glass.