The Eternal Nazi

Posted By Rolf Peter Sieferle On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,165 words

Czech version here [2]

Translated from Finis Germania by F. Roger Devlin

There are still myths and there are still taboos. Nudity and sexual practices of all sorts are no longer among them, any more than good old-fashioned blasphemy. The Christian God, for example, can be abused at pleasure without the slightest consequences. One taboo, however, remains immoveable: anti-Semitism. Criticism of Americans, Russians, the rich, industry, trade unions, intellectuals, men, politicians, even Germans, is cheap and can be formulated as sharply as one likes. Criticism of Jews, however, must be carefully packaged in the assurance that no anti-Semitism is involved. The reasons for this are obvious.

National Socialism, more specifically Auschwitz, has become the final myth of a thoroughly rationalized world. A myth is a truth that lies beyond discussion. It does not have to justify itself; on the contrary, any trace of doubt in the form of relativizing it amounts to a serious violation of the taboo which protects it. Hasn’t the “Auschwitz lie” been threatened with punishment as a sort of blasphemy? Behind all the emphasis on its “incomparability” do we not find the old fear of any revealed truth that it is lost the instant it submits to the enlightened business of historical comparison and justification? “Auschwitz” has become the embodiment of a singular and indelible guilt.

But what is meant by “guilt”? Literally, it concerns causation, but also a contamination, a defilement of what is right which can be eliminated or at least ameliorated through cleansing rituals. The criminal has polluted the legal community; the punishment, therefore, serves to cleanse it. In the case of especially great pollution, only the complete elimination of the criminal will do. He is given back to the elements: the fire which burns him, the water which drowns him, the air in which he is hanged and the earth in which he is finally covered. It is disquieting even to live in the same world where the criminal lives. He must, then, disappear, so that humanity is freed from the sight of his depravity. His very existence is unbearable. Thus the fanatical zeal with which, fifty years after atrocities occurred, old men who participated in them are still ferreted out.

Along with the individual guilt of the criminal, there is the collective guilt of his tribe or the community of which he was a part. This collective guilt can have neither a concrete criminological significance nor any significance for the maintenance of honor. It refers neither to the attribution of the deed nor the perpetrator, and for this reason cannot be canceled out through the elimination of the latter; in fact, it should not be. Rather, we are dealing with a guilt of metaphysical dimensions, comprehensible only in light of the older conception of original sin. The guilt of Adam, this transcendental man, corrupted the entire human race descended from him; at the same time, it was redeemed by the grace of God whose command Adam had violated. Man did not fall into the bottomless abyss of depravity; instead, in the very greatness of his guilt was demonstrated the greatness of the grace which preserved him. Guilt, repentance, grace and love are, therefore, inextricably bound together; they form an indestructible equilibrium within the divine economy of salvation.

From the collective guilt of the Germans, which derives from Auschwitz, there also follows an exhortation to permanent repentance, but in this secularized form of original sin the elements of grace and love are entirely absent. The German resembles not the man whose guilt is (if not undone, at least) compensated through God’s love, but rather the Devil, the fallen angel, whose guilt is never forgiven and who will remain in darkness for all time. Even the Devil, however, has a function within the divine economy: he forms the negative background against which the positive goodness of God stands out. In his negativity are concentrated all the defects of creation in such a way that God himself is unburdened of the painful questions concerning the justification of evil in this world.

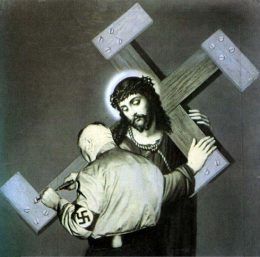

The German, or at least the Nazi, is the secularized Devil of the enlightened present. This autonomous, adult world needs him as the negative background against which it can justify itself. In this regard, there is a remarkable affinity between the German and the Jew, as the latter was seen in the Christian past. The second great crime of humanity after Adam’s fall was the crucifixion of Christ. True, this outrage was instantly annulled through the resurrection and salvation, but such salvation had at least one minimal requirement: faith. The Jews were those who not only committed this monstrous (if necessary) crime—they also refused to believe that Jesus was the Christ, thus rejecting the offer of salvation. This criminal obstinacy of the Jews was an enormous offense to Christendom; the very people among whom the Son of God had appeared refused to accept the salvific event associated with him. Moreover, since the conversion of the Jews formed a presupposition for the coming of the Kingdom of God in an eschatological sense, the Jews stood for the opposite of salvation, and thus became the embodiment of evil in the world.

The Jews’ stubborn refusal to accept the revealed truth of Christianity served as a reminder that humanity was not yet ready to abandon its sinfulness. So however furiously and thoroughly all heathen and heretics were detected and exterminated, there was never any thought (despite occasional persecution) of destroying Jewry as such. They were a painful but tolerated thorn in the flesh of Christendom. Since the Jews could take no part in Christian glory, they nested in the crannies of society as moneylenders and tradesmen. Here again we see an affinity with the Germans, who went from heroes to tradesmen, despised by the whole world and mindful of their own advantage.

The world obviously needs Jews or Germans in order to be sure of its own moral qualities. Yet in one respect there is a powerful difference: the Jews did not share the appraisal they met with from Christendom, whereas the Germans are the first to acknowledge their indestructible guilt—if only in such a way that the one who speaks of German guilt or responsibility usually exempts himself, since guilt is always recognized with reference to the unrepentant, i.e., others. Adam’s guilt was canceled within the terms of salvation history through the sacrificial death of Christ. The Jews’ guilt in crucifying the Messiah went unrecognized by themselves. The Germans, who recognize their own unredeemed guilt, must on the contrary disappear from the scene of actual history, must become an eternal myth, in order to expiate their guilt. The eternal Nazi will long decorate the workaday mythology of a post-religious world as the ghost of his crime. But the earth will only be purified of this disgrace when the Germans entirely disappear, i.e., become abstract “humanity.” But perhaps then the world will have need of other Jews.