Céline Goes Hollywood

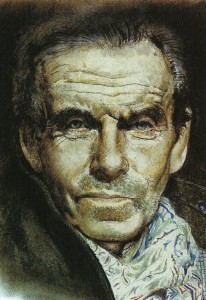

Posted By Margot Metroland On In North American New RightOne of the saddest episodes in the life of Dr. Louis-Ferdinand Destouches, alias Louis-Ferdinand Céline, came right after he published his first novel in 1933.

Voyage a la bout de la nuit (Journey to the End of the Night) was a succés d’estime from the start and before long a bestseller too. Surely it would be soon made into a major motion picture.

Céline expected that, anyway. He had many friends in the movie business, and he thought he wrote with a screenwriter’s eye.

Almost immediately Voyage caught the attention of Abel Gance, then a leading French director, who bought a short-term option. When Gance didn’t move ahead, Céline looked elsewhere. The book had almost immediately been translated into German and Czech. He went to Prague, where German director Carl Junghans showed an interest.[1]

But Céline’s real hope, all along, was to visit Hollywood and make a Hollywood movie. Among Hollywood’s many attractions was the fact that his longtime mistress, Elizabeth Craig, had gone home to Los Angeles the previous year and never returned.

In the end he got neither movie nor girlfriend, and plunged into a despair that colored the rest of his life.

Let’s begin with some itinerary notes from Louis-Ferdinand Céline et le cinema (2011) by French critic Marc-Henri Cadier. [2]

On 12 June 1934 Céline embarks for the United States. From New York he goes to Los Angeles, then to Chicago. On 28 August he is to return to Paris. In the course of his crossings he meets actors Jean Gabin—whom he would have found sympathetic—and Danielle Darrieux.

The purpose of the trip is not just the launch of the book in the United States, but also to make contact with Hollywood. It should also be noted: Céline had already established some footing there by sending a copy of Journey to Jacques Deval, the author of “Tovarich.” [Which shortly became the French movie Tovaritch (1935) in which Céline himself has a walk-on scene.]

Deval knows the film-industry milieu, has met the big players and intermediaries in the industry ; he goes back to Europe and brings actors and scenarios, and has now promised Céline that he’ll facilitate all negotiations. Later on, Deval says he wasn’t really interested in Celine’s book.[3]

Anyway, Celine’s main aim is to get to know Hollywood. On this subject, he writes [editor Xavier] Denoël on 12 July 1934 : “I have just signed a six-month option for Journey with Lester H. Yard [screenwriter and agent]. Of all the agents, he seems the most capable, the most rascally.”

But it was 1934. The dawn of a new, strict, Motion Picture Code from the Hays Office.[4] There were now real obstacles in bringing a book like Journey to the screen, with its violence and squalid settings. But perhaps, Céline hopes, this new Code just a passing fad? Hé bien!

As he says in his letter to Denoël: “The times are not very propitious to works of this genre. But maybe in six months the puritan rigors will be forgotten.” To Henri Mahé [5] he writes: “Here’s the nub of the film question. Only chastity and cheerfulness are to be tolerated. Figure it yourself.” He wonders: Does this famous modesty code of William H. Hays mean that virtue will rule forever in Hollywood? On the movie screens, at least?

24 July 1934: “It happens that my coming here has brought a lot of bad publicity, which I put up with to arouse the attention of the film people, the only ones who interest me. No doubt we’ll see offers during the winter. $20,000.”

So film people were the only ones to interest Céline?

A month later, 30 August, he writes a lady friend: “Nothing’s happening in American cinema. It’s all a journalistic concoction—nothing more. I came to United States for another reason entirely, very personal, and that’s it. There’s no way Journey can make it to film, for a thousand reasons. I never worked for Hollywood. They don’t know me either.”

What to make of this? Where’s the truth?

In reality this trip to the United States was not only motivated by the book publication and its film adaptation. There’s another reason, well established: to find Elizabeth Craig in Los Angeles. She was an American dancer with whom Céline lived for some years in Paris, but who had left the previous year. Céline wants to convince her to return to France.

After Céline dedicated Journey to her (incidentally, she once confessed to never having read a line of the book!), Elizabeth Craig had gone home and become Mrs. Ben Tankel. The despairing Céline realized the reconciliation was a pipe dream. In consequence Céline he showed irritation with her and made up stories, such as saying that “Elizabeth has given herself to gangsters.”

* * *

But just who was this Elizabeth Craig? Before Céline met her, Elizabeth Craig (1902-1989) had been a minor player in silent films in Hollywood. (Two Cecil B. DeMille films, Manslaughter, 1922, and The Ten Commandments, 1923; apparently in roles too minor to be included in cast lists at imdb.com, etc.) In New York she danced in the Ziegfeld Follies. With her parents in 1924 she went to Paris, where she studied dance.

She met Céline in Geneva in 1926 when he was a young physician working for the League of Nations. They would live together for seven years.

Of their relationship in Paris, an acquaintance remembered them as an “an idyllic couple, a bit conventional.” Elizabeth had red hair and green eyes, full lips. «Elle était charmante, brilliante et bonne» recalled the friend.[6]

Elizabeth occasionally made trips back home to see her family, and in 1933 she said her mother was dying. Celine saw her off, accompanying her on the train from Gare St-Lazare to Le Havre. He saved his railway ticket, and stuck it to the wall of their flat in Clichy. Clearly Elizabeth was expected to return. But she didn’t. Thus Céline’s sad journey the following year to retrieve her, using the convenient pretext of selling his novel to Hollywood. “She lives in a cloud of alcohol, tobacco, police, and low gangsterism, with a certain Ben Tankle [sic],” Céline wrote a friend, after seeing Elizabeth in California.[7]

Interviewed shortly before her death in 1989 by Alphonse Juilland, Elizabeth said she couldn’t really see spending her life with Céline because his interest in her was mainly physical. He would not have liked her when she got old.[8] And he was too much of a depressive, she said in a video interview.[9]

Elizabeth finally married Ben Tankel in 1936. The fact that he was a Jew continually piques the interest of commentators on Céline. “One of the reasons that pushed him to write Bagatelles pour un massacre,” writes Brami, in a typically pat observation.

Hunting down the source of Céline’s antisemitisme is a favorite game of critics. The subject has an eye-grabbing appeal. But it’s unlikely that Céline got that way because he lost his mistress to a fast-living quasi-mobster. In that video interview above (generously festooned with horrific cartoons), Elizabeth Craig says Céline was probably always that way.

* * *

A new book by Céline biographer Jean Monnier offers a somewhat saucier spin on La Belle Craig than we have usually been given.[10] Sensual and amoral, Elizabeth leaves Céline for Benjamin Tankel because Ben offers more money and fun. She denies that her real-estate mogul is a gangster, although his biggest client was Mafioso Jack Dragna.

Monnier’s Elizabeth Craig: une vie celinienne is frankly and unfortunately a work of imaginative fiction, inspired by the spindly threads of Céline correspondence and Elizabeth’s end-of-life interviews.

Life with Benjamin was a great pleasure party. . . His ambition was to make money in the fastest way possible, and spend it even faster. We went out almost every night. . . He demanded the best table and left huge tips. . . I was his trophy, and he showed me off with pride.

Not only is it a fictional memoir, but one in which verisimilitude is not its saving grace. We get scenes of Ben and Elizabeth guzzling champagne and caviar with Mickey Cohen and Bugsy Siegel. Gangland convictions and assassinations are dropped in oddly, as though ripped from old headlines, as are political and social issues.

In February 1942, three months after the Japanese attack, President Roosevelt signed a decree for the deportation of all the Americans of Japanese origin. Their goods were all to be confiscated by the War Time [sic] Civil Control Administration. However, the majority of this population was in agriculture, a field in which they excelled. On the eve of being deported, these farmers had no choice, finding a buyer was all they could do to save something.

What an extraordinary digression for an old chorus girl looking back on her life!

Actually this one is a plot device. Our fictional Elizabeth goes on to tell us that Benjamin and his mob friends were able to profit from the misery of the “deportees.” Even though it was paradoxical that Benjamin never saw the parallel between the “deportation” of the Japanese and the endless persecution of his own people, the Jews.

But anyway the episode has a happy outcome:

We worked hard and made a lot of money. Benjamin decided to treat me to a little luxury. He took an apartment in the Sunset Tower, Hollywood’s most chic address.

The depiction is comic and ludicrous, like Bertolt Brecht’s Chicago—but, I suspect, not intentionally so. The author is merely concocting a French-tourist version of America in which there is no real difference between fact and fiction. He gratuitously name-drops people and places, often with telling errors. (Siegel’s mistress Virginia Hill is “Virginia Hills”; McCarty Drive in Beverly Hills is “McCarthy Drive.”)

Monnier has obviously seen a lot of films about gangsters and Hollywood. No doubt he wrote this in expectation of inspiring yet another one. Céline may make it into the movies yet.

Notes

1. Carl Junghans, aka Karl Younghans, was a pro-Communist actor and director in Berlin the 1920s, then went to Prague, and back to Germany for a while where he worked with Leni Riefenstahl on Olympia (1936). Then, to France; to the USA after the start of the war; and finally back to Germany. He is said to have had an affair with Vladimir Nabokov’s sister-in-law and to be a possible inspiration for Nabokov’s character Humbert Humbert. See http://nabokovsecrethistory.com/news/meet-carl-junghans-propagandist-literary-inspiration-camera-obscura-lolita [4]

2. Marc-Henri Cadier, Louis-Ferdinand Céline et le cinema. St-Etienne, France: Editions M.H.C. 2011.

3. A slightly different account appears as “Impossible Voyage” in La Rumeur Mag [5], 2014.

4. Although a Motion Picture Production Code from the “Hays Office” had been in existence since 1930, it did not have any real teeth until July 1934. At that point, studios were forbidden to release commercial films that did not have a Production Administration Code certificate of approval. Thus Céline was pushing his racy novel. just as the strict code came into effect. It was all over the pages of Variety during Céline’s visit. Hélas!

5. Henri Mahé, 1907-1975. Painter and film director, friend of Céline.

6. Éliane Tayar, quoted in Emile Brami’s Celine à Rebours. Paris: Archipoche. 2011.

7. Brami, Ibid.

8. Alphonse Juilland, Elizabeth and Louis. Paris: Editions Gallimard. 1994.

9. Elizabeth Craig parle de Céline [6], on YouTube.

10. Jean Monnier, Elizabeth Craig: une vie celinienne. Paris: Robert Laffont. 2018.