To Kill a Nice, White Society:

Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird

Posted By

Adna Bertrand Rockwell

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

One of the greatest metapolitical efforts that has ever been brought to fruition is, in fact, the work of our mortal philosophical enemies – that is to say, Harper Lee’s novel To Kill a Mockingbird, which was published in 1960 and then turned into a popular film in 1962. The book and the film are quite similar, and this review covers both endeavors. As usual, the book is better than the film, but both works use the same methods to move towards the same metapolitical goal of “civil rights” and white dispossession.

The fictional works of white advocates have yet to surpass the bar set by Mockingbird. Most racially-aware fiction is futurist-dystopian or science fiction, and while these genres well convey the problems involved and contribute all manner of ideas on the subject, they still fail to measure up to Mockingbird’s heavyweight metapolitical punching power. What, then, makes To Kill a Mockingbird so powerful? After some thought, I concluded that there are four elements that really made this story work.

. . . But First, the Plot

This review is written under the assumption that most of its readers have either read To Kill a Mocking Bird or seen the film, so this summary will be brief. Throughout Mockingbird, there is rich character development and a good portrait of small-town Southern life. The story takes place in fictional Maycomb, Alabama during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The story’s narrator and protagonist is a precocious, tomboyish girl named “Scout” Finch, who spends her time playing with her brother Jem and their friend Dill. The Finch siblings’ mother has died and they are being raised by their father, Atticus Finch, who is an attorney.

The three children explore their town in an innocent way. They become interested in a recluse named “Boo” Radley. It turns out that this socially isolated man is attempting to reach out to the kids by leaving friendly gifts for them in tree hollows in their neighborhood.

In the meantime, Atticus Finch is assigned to defend a black man named Tom Robinson from a rape accusation by 19-year-old Mayella Ewell. The Ewell family are low-class “white trash” who live in grinding poverty. Robinson’s trial becomes the talk of the town. Atticus carries out his legal duties with dignity.

During the trial, Atticus weaves a story implying that Mayella tried to put the moves on Tom Robinson and was beaten by her own father for the cross-racial encounter. The Ewells are humiliated. Robinson is found guilty regardless, and is later “killed attempting escape.” When Bob Ewell attacks the Finch children in revenge for the humiliation at the trial, they are rescued by “Boo” Radley.

Element #1: To Kill a Mockingbird is a Very Good Story First – With Message Second

To fully understand Mockingbird’s power, one should first contrast it with badly-done metapolitical works that attempt to convey a message – namely, Christian films. By “Christian” I specifically mean Baby Boomerist, Evangelical Protestant films – not something produced by a filmmaker who creates an artistic movie with a Christian theme like Mel Gibson or Martin Scorsese. The best way to collectively describe most of those works is “crap.”

A very partial list of Christian – i.e. American Evangelical Protestant Baby Boomerist (AEPBB) – movies that are crap include God’s Not Dead (2014), Fireproof (2008), and War Room (2015). This list is partial because all AEPBB movies are crap, but the three movies mentioned have entered mainstream consciousness. What makes these movies so bad is that:

- The outcome of all AEPBB films must end with the predetermined message of the AEPBB religion. In other words, the conflict must be resolved by the protagonist “finding Jesus” for the first time, or “rededicating” his life if he “found Jesus” earlier in his life. Each movie is thus a sermon with a film built around it.

- Christians (AEPBB) fundamentally bend to the reigning liberalist ideology of the immediate post-war years in which the Baby Boomers were born. This includes fundamental support for feminism (Fireproof) or racial integration (War Room). As a result, there is no real insight into any issue.

- Because there is no insight into the underlying issues, the AEPBB, Altar Call [2]-style endings are unsatisfying. “Finding Jesus” or “rededication to Christ” are only simplistic magic acts. The actual systemic problems, such as having a faithless wife (as in Fireproof), remain.

If To Kill a Mockingbird were an AEPBB film, the good characters would be entirely on board with racial integration from the get-go, and Atticus Finch would offer a long-winded speech[1] [3] imploring all whites to get on board. The jury passing judgement on the accused Negro rapist would not convict him because one juror would have “all the answers,” and the rest would listen passively to him. To Kill a Mockingbird would be crap and nothing more would be heard of it.

However, To Kill a Mockingbird is ninety percent story, with a nuanced, dual plot involving, on the one hand, a nostalgic, feel-good, emotional look at small-town Southern life and a trial involving a clearly innocent Negro. It is only ten percent message, and that message’s delivery is masterfully achieved.

Element #2: The Fictional Tricks Used to Package To Kill a Mockingbird’s Message

To Kill a Mockingbird’s metapolitical intent is to support “civil rights,” i.e., integration of blacks into white, civilized society regardless of the costs. It does so by a series of fictional tricks.

The first trick is To Kill a Mockingbird’s genre: that is to say, small-town nostalgic fiction. This genre is an extremely soft, emotional, and escapist form of fiction. One of the genre’s pioneers was a white advocate, William Dudley Pelley [4], who wrote stories about a fictional town called Paris, Vermont [5]. Other fiction of this genre includes Little House on the Prairie [6] (both the series of books and the TV program), The Andy Griffith Show [7], The Dukes of Hazzard [8], and The Waltons [9]. This genre has the ability to endorse radical social policies of a dubious nature by projecting them into an imaginary, rose-colored past. “Civil rights” is, in fact, a social policy that has produced a great deal of stress in modern life, but in Mockingbird, civil rights are just fine, for they are what should have happened in the dew-covered, innocent world of small towns and childhood.

To Kill a Mockingbird’s next trick is that its world has been set up in such a way that its metapolitical message works without a hitch. Atticus Finch is a widower. As such, he is able to carry out his duties free of a nagging wife, or a wife who asks hard questions about rapists. Next, the accused rapist is conveniently given a disability: an unusable left hand, thus rendered after it was caught (of all things) in a cotton gin when he was 12. Tom Robinson is also old enough to be beyond the age bracket for most criminals. And although Mayella Ewell is an attractive young woman, there are no other men trying to court her. She is so lonely that she develops a crush on a married black man. In the real world, it is more likely that a woman like Mayella would be trying to become the next Mrs. Atticus Finch.

Furthermore, the character of Atticus Finch is what upper-class whites see as an idealized version of themselves. This hides the fact that Atticus’ strategy during the trial is a shifty legal smokescreen no different from O. J. Simpson’s Dream Team. Robinson’s disabled-hand defense was replicated in real life by O. J.’s “glove that didn’t fit.”

It is also important to note a missing character in this story: an antagonist who conveys a great truth, or otherwise puts forward his reasoning. In the excellent 1953 epic Shane, the antagonist very much gives his side of the story [10]. In 1980’s The Empire Strikes Back, the antagonist, Darth Vader, famously says [11], “. . . [W]e can end this destructive conflict, and bring order to the galaxy.” Emperor Palpatine expresses similar sentiments [12] in 2005’s Revenge of the Sith.

In To Kill a Mockingbird, nobody offers up a defense of white supremacy in the South, although there was indeed a large body of race realist literature going back to Thomas Jefferson. Someone should have said, “Humiliate Mayella Ewell and all crime involving blacks will be more difficult to manage.”

Its final trick is that, unlike AEPBB films, the message in Mockingbird is in what is shown but not said. The injustice of Tom Robinson’s trial is seen, but not commented on. The “racists” in the town are uneducated trash like the Ewell family, or else are regular people, such as the citizens on the jury, who are following convention although it is clearly against their conscience to do so. Again, it is shown, but not commented upon.

Element #3: Hard Work & Omertà

Part of To Kill a Mockingbird’s realism derives from the fact that the book was semi-autobiographical. Harper Lee really did grow up in a small Southern town. The character of Dill was believed to be the literary great Truman Capote, who had been an actual childhood playmate of Lee’s. Indeed, many suspected that Capote was the one who really wrote [13] Mockingbird.

This rumor dogged Harper Lee for the rest of her life. To Kill a Mockingbird has even been run through computer algorithms [14] to verify if the narrative “voice” therein is Lee’s or someone else’s. Part of the mystery is that Lee never wrote another book during her lifetime. She also gave very few interviews. In one of the few, which she gave to WQXR in 1964 [15], she was not very insightful. In that broadcast, she claimed that she was working on a second novel, but that the going was slow. She also claimed that she was writing for days on end. In retrospect, everything that she said was a smokescreen.

In 2015, only months before Lee’s death at age 89, a “sequel” to Mockingbird was published: Go Set a Watchman. The highly-anticipated sequel was a bestseller, but also a major disappointment, although it did fill in the gaps [16] of how Mockingbird really came about. Watchman was really a first draft of Mockingbird. Indeed, the speculation that Harper Lee hadn’t really written Mockingbird was somewhat true: Lee had a great deal of help from an upper-class Quaker woman from Brooklyn named Therese von Hohoff Torrey, who was known professionally as Tay Hohoff. Hohoff was an editor who nursed the manuscript along for three years.

Neither Harper Lee or Ray Hohoff ever discussed their collusion publicly. There was only what the mafia calls omertà – namely, silence regarding the production of the novel. The legend of Mockingbird’s composition was thus a product of omertà, and was the result of very hard work over a very long time.

Element #4: To Kill A Mockingbird, the Goals of the Political Elite, and Omertà

As we now know, the promised “dream” of the “civil rights” movement of the 1950s and early 1960s turned into a disaster. The political elite of the generation prior to Harper Lee’s – Henry Ford, Madison Grant, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and so on – were all in today’s terms quite “red-pilled,” but for some reason[2] [17] the political elite which had fought the Second World War moved away from the wisdom of their elders. To Kill a Mockingbird fit in with the agenda of integration and civil rights that was being endorsed by the new, post-war elite.

Hohoff’s tender shepherding of Mockingbird through its long, hard production slog makes sense within the context of support from the political elite. A well-written pro-integration novel was sure to get reviews in The New York Times and other notable venues. Additionally, support from the elite makes the fact that the book won the Pulitzer Prize, as well as the fact that a film adaptation was quickly made featuring A-list actors, easier to understand.

[18]

[18]“Yer Father’s passin’.” Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck) is honored by blacks when they stand for him after the verdict. This scene lands a heavy metapolitical blow. White supporters of “civil rights” believed they would get similar adoration from blacks. (They didn’t.)

However, the omertà continues. To Kill a Mockingbird was metapolitics for the Civil Rights Movement, but nobody asked Harper Lee what she thought of the direction that the movement took. In the real world, a situation involving a cross-racial rape would go something like this:

- The rape victim, Mayella Ewell, would have grown up poor, but would have become a teacher or social worker. She’d be in her thirties – old enough to think that she didn’t need help around blacks.

- If Mayella’s family was intact, her father might have had an alcohol problem, but he wouldn’t have been abusive. More likely, she’d have grown up in a broken home with no father at all.

- Tom Robinson would be a teenager with a long rap sheet prior to the rape.

- Mayella Ewell may or may not have survived her encounter with Tom Robinson.

- If the trial had made it into the national consciousness, Tom Robinson would have been “Obama’s son,” and he’d be acquitted regardless of the evidence. If the trial only made it into the “Right-wing” media, his conviction would be overturned on appeal, or the Governor of Alabama would have commuted the sentence as a strike against “racism.”

- If pardoned, acquitted, or freed, Tom Robinson would continue with a life of crime. Like Rodney King, he’d die in an undignified way, or eventually be returned to prison upon conviction for a different crime.

- “Boo” Radley would never have left his house or had a positive interaction with the Finch children.

An Inspiration for White Nationalist Fiction?

Part of To Kill a Mockingbird’s power is that it cleverly puts a radical social experiment into a story that is otherwise ninety percent nostalgia. White Nationalist fiction writers should take inspiration from this story and seek to make use of its tricks toward more just ends. Several possible subjects from history include:

- A child’s view of King Philip’s War, which made New England something like a white ethnostate.

- The Paxton Boys’ attack on Indians in Pennsylvania; perhaps have a young boy join the effort. The Paxton Boys made western Pennsylvania into a white ethnostate, but were criticized by the political elite in Philadelphia.

- A young girl on a Southern plantation helps freed blacks move to Liberia.

- Young whites move from an integrated school in Boston after integration.

- A rancher’s kid must deal with illegal immigrants in south Texas after President Reagan’s amnesty.

- The child of a fallen 9/11 firefighter is forced to deal with violent Muslim immigrants in the schools.

[19]

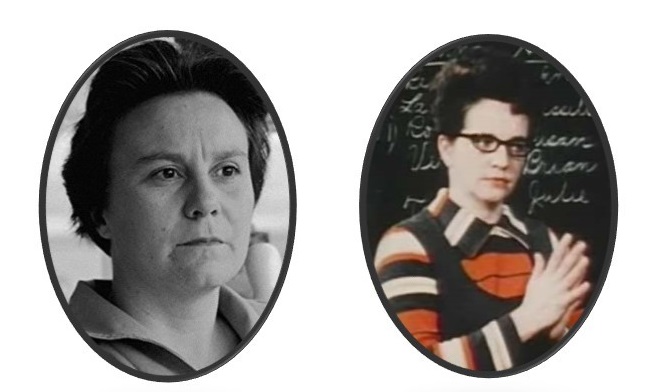

[19]Harper Lee (left) and Jane Elliott (right) in the 1960s. Elliott pioneered a method of anti-white humiliation and diversity training after Martin Luther King was assassinated. Harper Lee wrote the metapolitical work that caused whites in positions of authority to turn a blind eye toward black criminality. Both women have hard faces which convey a sense of cruelty and barrenness.

Adna Bertrand Rockwell was inspired to write this article after his trainer, Kyle, discussed To Kill a Mockingbird in great detail during a workout session.

Notes

[1] [20] For an example of a long-winded, on-message statement, here [21] is the prayer scene from War Room.

[2] [22] Perhaps the biggest American mystery is why the white political elite at the center of the 1960s Democratic Party embarked on the tragic programs that eventually dispossessed American whites in their own society. One person at the center of this is Nicholas de Belleville Katzenbach. He worked in the Kennedy administration and became US Attorney General under Lyndon Baines Johnson. Katzenbach was what Wilmot Robertson called a “member of the American Majority.” His ancestors in the de Belleville family stretched back to Nicholas de Belleville, a doctor who had served on the staff of the Continental Army’s Cavalry Chief, Count Casimir Pulaski, in the Revolutionary War. Katzenbach’s father, Edward, had been New Jersey’s Attorney General, while his mother was the President of New Jersey’s State Board of Education. His uncle, Frank Katzenbach, had been the Mayor of Trenton, New Jersey. He was also descended from Moore Furman (1728-1808), Trenton’s first Mayor.

Katzenbach was a combat veteran. He had been a First Lieutenant in the US Army Air Force, and was taken prisoner after the B-25 in which was serving as navigator was shot down. Katzenbach’s background was thus in tune with that of most of the senior officials in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. Most had served in the war as officers, and the plurality were men descended from prominent figures in American history.

Katzenbach’s memoir, Some of It Was Fun (2008), offers no explanation for why valorous, high-ranking men of the 1960s embarked on the Civil Rights Movement other than “muh rights,” and offers no assessment of the movement’s effects.