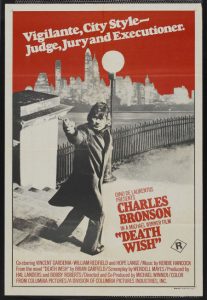

The Original Death Wish: A Review

Posted By Spencer J. Quinn On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledDeath Wish

Directed by Michael Winner

Screenplay by Wendell Mayes

Starring Charles Bronson, Hope Lange, Stuart Margolin

1974

By the early 1970s, Americans had begun to notice a change in their big cities. After the Civil Rights movement and the 1965 Immigration Act, the multiracial rot – the inevitable by-product of the Left’s ascendancy in the West – began to set in. Cities that were once clean, safe, and orderly became much less so in fairly short order. Americans were not complaining about muggings, rapes, and murders as much in 1960 as they were a decade and a half later. They also didn’t feel as if they were entering another country every time they walked three blocks to buy groceries.

The original Death Wish film, released in 1974, was, on one hand, a way to capitalize on these newfound feelings of insecurity and alienation which were perplexing the lives of millions of white Americans at the time. On the other, it did give legitimate, if somewhat oblique, expression to these feelings, so much so that the film quickly became iconic despite mostly poor reviews, and spawned four sequels over the following twenty years, as well as a big-budget remake that was recently released. The plot is straightforward: A solid citizen discovers that thugs have murdered his wife and raped his daughter in his New York apartment, and he then acquires a gun to take revenge on the streets as a vigilante. Given the film’s success at the box office, it is safe to conclude that many Americans, especially the white ones who fondly remembered a better past, strongly identified with such a character.

Forty-five years after its release, the film’s flaws have become almost embarrassingly apparent. Death Wish is by no means a great film. Charles Bronson, who plays the main character, Paul Kersey, does the tough, sullen hero routine well. But when required to act alongside real thespians, his lack of range becomes as painfully apparent as the Fu Manchu mustache which stretches across his ruggedly handsome face. The dialogue, which is clunkily written, goes from cheap and clichéd (“Beautiful place, Tucson. They can breathe out there.”) to Right-wing agitprop (“What about the old American social custom of self-defense? If the police don’t defend us, maybe we ought to do it ourselves.”), but otherwise doesn’t distinguish itself (with one exception, discussed below). And the over-the-top, modernist score by Herbie Hancock intrudes upon the narrative far too often, and does the most to date the film.

Still, director Michael Winner has a decent sense of where to put the camera and how to move it. At around ninety minutes, the film is rarely boring, and takes us from the beginning through to the end competently enough. But the suspense it creates through the editing, performances, and direction rarely rises above the ordinary. When compared to Taxi Driver, a similar urban drama from the period, Death Wish lacks inspired cinematic vision and a virtuosic lead performance. Also unlike Taxi Driver, however, Death Wish does not focus on gore, and instead attempts to present life as it really is. People remember Death Wish not for the craft that went into it, but for its meta-narrative – that is, its gritty, brutal, and ultimately ironic take on vigilantism in a world growing more dangerous and unfamiliar by the day.

When presented with a story as mired in realism as Death Wish, we first want to determine how real it is. If verisimilitude is one of the story’s selling points, then it is fair game for any sober assessment of the film. For example, we might give The French Connection, another urban drama of the period, a bit more leeway, since that film identifies as an action-thriller and contains recognizable, if unrealistic, tropes belonging to its genre – for example, daredevil cops and edge-of-your-seat car chases. Death Wish, on the other hand, is about one guy who sees his family destroyed and then turns into a killer. Within such limited parameters, most everything in Death Wish lives up to the mundane, low-grade terror that denizens of big cities were learning to live with in 1974. And this is to Michael Winner’s great credit. Whether we are on the streets, in cafés, police stations, subways, offices, apartments, or hospitals, Death Wish succeeds in producing the honest feel of a disturbing news documentary. Most importantly, Bronson, with his hard, pitiless stare, easily convinces us that he could kill – you. Me. Whoever. And he won’t lose too much sleep over it as long as he knows you’re a criminal.

One minor quibble: Kersey has a suspiciously easy time getting mugged. Whenever he goes out alone at night, hunting for thugs, it seems there are teams of them just waiting to pounce. It’s as if the prime targets of muggers back then were burly, tough-looking men wearing long jackets in which they could pack all manner of heat. Don’t muggers usually hit the easy targets? Still, it’s a film, so some disbelief has to be suspended.

My biggest quibble, however, has to do with race. Just about half the muggers Kersey encounters are white. In two cases we have interracial gangs reminiscent of The Warriors, a much more fanciful urban drama which came out a few years after Death Wish. Most tellingly, however, the three men who attacked the Kersey women at the beginning of the film are all white. The credits refer to them as “freaks,” and indeed, they behave like horny hooligans once they break into the Kersey household. The rape and murder scene, while not handled as deftly as its counterpart in A Clockwork Orange, meets the film’s high standard of realism well enough. (Although casting a young and dweeby Jeff Goldblum as one of the perps was a dodgy call, in my opinion.) But the fact that a crime typically committed by blacks (gang rape) is portrayed as being committed by whites stinks of Hollywood social manipulation. That’s not how it is. It’s how they want it to be or how they want you to believe it to be. And that usually ends up with big, bad whitey pulling the strings for everything evil under the Sun.

It was at this point that I paused the film and checked the filmmakers’ bios online. Of course, Bronson was all gentile, and so was producer Dino De Laurentiis. The Wiki pages of co-producer Bobby Roberts, screenwriter Wendell Hayes, and novelist Brian Garfield remain inconclusive (which usually means not Jewish), while co-producer Hal Landers doesn’t even have a Wiki page. It seems the only chosen one behind the scenes with major clout is Winner himself. Then again, Winner, a British Jew, was a big fan of Margaret Thatcher, and once claimed that as Prime Minister he would be “to the Right of Hitler.”

Whatever on that.

With at least some faith restored, I persevered and kept track of all the bad guys Kersey met for the remainder of the film. About half were black, and of the remaining whites, a couple of them appeared to be strung-out junkies rather than cruel and exploitive villains like Goldblum’s gang early in the film. It dawned on me fairly quickly that, despite the questionably high number of white muggers, this film is not anti-white at all. Yes, it places blacks conspicuously among authority figures (cops, mostly) as well as among the victims. But this, I believe, remains within the bounds of 1974 reality. At one point in the film, as New Yorkers are becoming emboldened by Kersey’s vigilantism, one elderly black woman (and perfectly innocent soul) fends off a pair of black muggers with a hatpin. In an amusing news interview, she goes off on a rant so ebonically loaded that I’m sure it charmed mainstream audiences back then as much as it would race realists today. Such a speech, of course, would be well beyond the limits of modern political correctness, and would likely end up on the cutting room floor, if it could be filmed today at all.

An interlude about midway through the film convinced me that Death Wish was not just anti-anti-white, but indeed pro-white. A still-grieving Kersey goes on a business trip to Tucson, Arizona to meet with a landowner named Aimes Jainchill (played impeccably by Stuart Margolin). Kersey is an architect and needs to come to terms with Jainchill about how he’ll develop his land into a proper neighborhood. As soon as Kersey arrives, Jainchill takes him to the hilly desert to give him a feel for the land before beginning his sketches at the office. Like many a country gentleman, he’s tall and he’s got the drawl. He’s got a tan suit, big cowboy hat, cowboy boots, two big pairs of steer horns on his big station wagon, and cowhide upholstery. Amid mooing cows and cowboys riding on horseback, Jainchill tells Kersey he wants to keep the hills – despite the New Yorker’s worry about “wasted space” – and is keenly interested in developing quality homes that “won’t turn into slums in twenty years.” He clearly loves the land and aims to protect it.

Keep in mind, this is a white thing. Typically, it’s been European whites – not blacks, Hispanics, or Indians – who identify with the countryside through agriculture and by raising livestock. Aimes Jainchill serves as the perfect avatar of the white soul, a throwback to the days of the American frontier, where hard men had to defend their families and communities from wild animals and the elements, as well as from criminals. Yet Jainchill is no hillbilly or redneck. He’s friendly, confident, intelligent, and articulate. Moreover, he takes a liking to Kersey and brings him to the gun range, where he spouts NRA talking points about Second Amendment rights. He does this so eloquently and idiosyncratically that it rises above mere dogmatism. I don’t know if this is due to inspired screenwriting, first-rate acting, or both, but the dialogue coming out of Jainchill’s mouth sparkles. When inviting Kersey to come to his club, he says, “It might amuse you, though. Being from New York, maybe you never seen a club like this. It’s a gun club. We shoot guns.”

For once, Hancock’s score is subtle: an eerie tone, just north of our ability to hear it, to underscore our foreboding and excitement. You see, after what happened to Kersey’s family, the audience is craving for revenge. And Aimes Jainchill, God bless him, is just the man to remind our hero how to take it.

So goddamn much hoopla from the gun control people. Half the nation’s scared to even hold a gun! You know, like it was a snake that was gonna bite you or something. Hell, a gun is just a tool, like a hammer or an axe. Wasn’t long ago it used to put food on the table, keep foxes out of the chicken coop, rustlers off the range, bandits out of the bank. Paul, how long since you held a pistol in your hand?

That Jainchill gives Kersey the very pistol he uses to clean the streets of scum later in the film supports this theme of Kersey getting back to his white roots. The sympathetic treatment all the other white characters in Death Wish receive also reinforces this notion. Kersey works in a fashionable office, and his boss is perfectly nice. So is Sam, one of his more urbane and aristocratic colleagues. Yet Sam is as disgusted with crime as Kersey is, and proposes radical solutions at which I’m sure even Aimes Jainchill would balk. Police inspector Ochoa (in an inspired performance by Vincent Gardenia) might resemble the tubby, hard-nosed detective stereotype a little too closely. Still, he is forced to tackle the tricky dilemma of fighting vigilantism when vigilantism is actually reducing crime on the streets. In this case, he handles it like a thinking, feeling human being, and not as a stereotype. Even Ochoa’s subordinate, a tall, ugly white guy with an even uglier mustache, gets treated fairly. All the signs are there for this person to be a brute, but he’s not. He’s just gruff and irritable. And who isn’t gruff and irritable sometimes, right?

As if this weren’t enough, at a party we overhear the following bit of dialogue between a white man, a white woman, and Sam:

Man: I’ll tell you one thing—the guy’s a racist. You notice he kills more blacks than whites.

Woman: Oh, for Pete’s sake, Harry, more blacks are muggers than whites. What do you want us to do? Increase the proportion of white muggers so we’ll have racial equality among muggers?

Sam: Racial equality among muggers? Ha, ha! I love it!

You know what? I love it, too. The filmmakers did not have to include this little snippet, but they did. In doing so, they were signaling to white people that they understand. Crime is not something whites bring to the table, certainly not in great civilizational hubs like New York City. No, this rot has been perpetrated mostly by intruders, by blacks and Hispanics especially, and it will be up to whites alone to deal with it.

When stripped to its essence, Death Wish and the Paul Kersey character personify 1970s white resistance to the multiracialism foisted upon them in the 1960s. There could be no black or Hispanic Paul Kersey, since such a man would spend most of his time killing his own. It’s a fact of life that minorities with a predilection towards crime must downplay the negative effects of crime in order to protect their standing in the nation at large. The biblical justice meted out by Kersey would have no place in their communities. Remember, Kersey doesn’t leave bad guys tied up with a note for the police, like Spider-Man. No, no. He just executes them. If they’re running away, he shoots them in the back. If they’re writhing on the pavement, he pumps an extra bullet into their bellies for their trouble. He doesn’t care. And if the ironic ending of Death Wish tells us anything, it’s that the filmmakers and audiences don’t care either. If you prey on people, then you deserve to die. The end.

Such primeval retribution represents the heart of Death Wish. Throughout the film, and the near half-century since its initial release, it pumps hard and it pumps fast. And not once does it bleed.

Spencer J. Quinn is a contributor to Counter-Currents and the author of the novel White Like You [2].