Europe Endless:

Kraftwerk on Tour in 2018

Posted By

John Morgan

On

In

Counter-Currents Radio,North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

6,221 words

[1]Audio version: To listen in a player, use the one above or click here [2]. To download the mp3, right-click here [2] and choose “save link as” or “save target as.” To subscribe to the CC podcast RSS feed, click here [3].

[1]Audio version: To listen in a player, use the one above or click here [2]. To download the mp3, right-click here [2] and choose “save link as” or “save target as.” To subscribe to the CC podcast RSS feed, click here [3].

On Wednesday, February 21, I was fortunate enough to be able to see the landmark German band, Kraftwerk, in concert in Budapest, nearly twenty years after I first saw them perform in Detroit in June 1998, and thirteen years after I saw them for a second time, also in Detroit, in 2005.

It was a great experience, of course, although also a reminder of the fact that Kraftwerk has become more of a piece of music history than a living, evolving group of artists, given that they have released next to no new music in over thirty years. Indeed, their reputation rests entirely on six albums and one single that were released over a twelve-year period between 1974 and 1986.

But this brings to mind Brian Eno, who said of the first Velvet Underground album that it “sold only 30,000 copies in its first five years. Yet, that was an enormously important record for so many people. I think everyone who bought one of those 30,000 copies started a band!”

Kraftwerk’s albums sold considerably more than 30,000 copies in their heyday, but it’s equally true that they served as an inspiration to countless other musicians and bands as diverse as David Bowie, Joy Division, Depeche Mode, Blondie, and Afrika Bambaataa, to name only a few. So, as legends who number among the most influential bands of the twentieth century, and who practically invented the techno genre, I certainly wouldn’t begrudge them taking their show on the road yet again despite the absence of new music.

As someone who grew up with the belief that any type of music other than classical was an inferior, if not degenerate, cultural form not even worth hearing, it wasn’t until I went to university, and was compelled to have roommates and apartment-mates, that I was forced to listen to music that had been produced after 1950, and discovered, to my pleasant surprise, that there was actually just as much depth and enjoyment to be had in other forms of music. I was first introduced to Kraftwerk by friends in 1996, and thought it interesting, but my love for their style was firmly cemented following an epic acid trip in January 1997 during which we listened to Trans-Europe Express, and the music seemed to perfectly articulate my understanding of what Europe is, in all its historical and atmospheric reality (and that was before I had ever set foot there; I’m pleased to say that when I finally got there, my impression was confirmed).

Kraftwerk appealed to me on many levels. First of all, as I was already a Germanophile, Kraftwerk’s sound and aesthetic are extremely German (and, to a lesser extent, European) – everything from the lyrics to the style to their album covers screams extreme Germanness. There was also the fact that Kraftwerk have always been experts at treading the line between deadly seriousness and satire to the point where you’re not sure which is which – something which Laibach [4] was to emulate, and take to much further extremes, in later years. It was as well the sheer power and polished nature of their music – although apparently simple on the surface, it in fact consists of many layers of sound working seamlessly together, and each song, upon repeated hearings, shows clear signs of having been very carefully constructed and honed down to the last detail. In that, it resembled classical music more than the average pop song. And, of course, there is the fact of their extremely distinctive sound – very mechanical, and yet somehow still very human, and capable on occasion of stirring deep feelings. There is also an almost child-like innocence to their aesthetic; in an age when most pop musicians seem to be in a contest to see who can be the most transgressive, Kraftwerk’s aesthetic, both musically and in presentation, has always been doggedly benign – one could indeed say, conservative.

Kraftwerk emerged as part of the rise of a new German musical culture in the late 1960s, just as a vibrant experimental music scene was beginning to take shape in West Germany in reaction to the dreadful state of German music at the time. Since the end of the Third Reich, West German popular music had been largely a product of the “Year Zero” of 1945, after which everything traditionally German had been cast under a pall of suspicion. As a result, German pop music of the 1950s and ’60s was mostly vapid and vacuous, being either plastic imitations of British and American bands, even to the extent of singing in English and having English band names, or else came from the genre of schlager (hits) music, which consisted of syrupy-sweet sentimental lyrics laid atop very simple tunes.

By the late 1960s, however, a new generation of German musicians was rising which had been born too late to remember the horrors of the war, occupation, and denazification. These young musicians were often classically trained, but were also interested in rock from the Anglophone world, and they were looking to break new ground of their own, part of which was their desire to explore the possibilities of using electronics in making music. The British press mockingly dubbed this new genre “Krautrock” at the time, a label which stuck, but many of the bands that emerged from it went on to become legends: Amon Düül II, Ash Ra Tempel, Can, Cluster, Klaus Schulze, Neu!, Tangerine Dream, and my personal favorite (besides Kraftwerk), Popol Vuh, which composed several of the soundtracks for Werner Herzog’s early – and best – films. None was to attain the level of fame and influence that Kraftwerk were destined to reach, however.

Electronic music was something which was only just beginning to emerge in the 1960s as something more than just a curiosity for avant-garde composers, as it had been earlier in the twentieth century when musicians, including some of the Italian Futurists [5] and Pierre Schaeffer, who developed music concrète [6] in France, produced music by manipulating recorded sounds via electronics. The 1960s witnessed the rise of electronic musical instruments which could generate their own sounds – original sounds which cannot be produced in nature or by any classical instrument. These new devices included such instruments as the Moog synthesizer, the vocoder, and the drum machine.

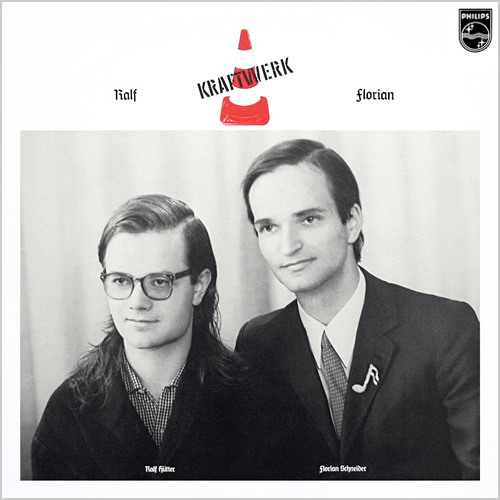

Kraftwerk was originally the brainchild of two musicians, Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider, music students who met while studying at the Robert Schumann Hochschule in Düsseldorf in the late 1960s. Düsseldorf, which has been Kraftwerk’s base of operations from its origins up to the present day, has long been the heart of Germany’s heavy industry, and Kraftwerk’s music most definitely reflects this backdrop in its atmosphere and rhythms. Indeed, Kraftwerk were among the first musicians to incorporate industrial sounds into their work, thus making them pioneers in the industrial genre, among others.

Hütter and Schneider were already performing under the name Kraftwerk – German for “power plant” – very early on, although when they produced their first album, Tone Float [7], it was released on the British RCA Victor label, and the company felt that buyers and listeners wouldn’t respond well to the foreign name. As a result, they went by the name “Organisation” for this album only. Tone Float, which was released in 1969 (and has never been reissued except as a bootleg), bears almost no resemblance to the sound for which Kraftwerk were to become famous, being more in the spirit of 1960s psychedelic jazz, and features little in the way of electronics apart from the use of an electric flute and violin by Schneider, and a Hammond organ.

Kraftwerk’s next three albums show their gradual evolution into the band that would make musical history. They released Kraftwerk [8] in 1970 and Kraftwerk 2 [9] in 1972. Although still very different from their later style, with some songs resembling psychedelic rock, and in some cases what later came to be known as ambient music, some of the elements that came to define the group already appear on them, including a much greater use of electronics and the sampling of industrial sounds. (The driving, drum-machine generated beat of “Ruckzuck,” which appears on Kraftwerk, presages their later techno, and those from my generation might recognize it as having been used as the theme song for the PBS series Newton’s Apple during the 1980s.) The third, Ralf and Florian [10], remains in a similar style, but brings them yet further towards their mature sound, with increased use of synthesizers. Kraftwerk hasn’t performed any of these songs since 1975, and none of these albums have been officially rereleased since they were issued on LPs in the 1970s, although they have been widely available as bootlegs since the 1990s. The band seems to regard them as juvenilia (Schneider once referred to them as “archaeology”), but to those who love Kraftwerk or electronica more generally, they are worth hearing.

[11]

[11]It was with 1974’s Autobahn [12] that Kraftwerk finally hit upon their distinctive sound, and that album is the first in what could be called the “Kraftwerk canon.” The title song is a 23-minute sonic odyssey depicting, well, a trip down an autobahn in a car. In addition to being the first example of their fully developed sound, characterized primarily by minimalist, repeating electronic rhythms, melodies, and lyrics (most of Kraftwerk’s previous songs had been solely instrumental), it also marked the beginning of the thematic concerns with which they were to remain preoccupied from then on: the celebration of technology and industry, and a naïve, almost child-like romanticization of these elements which in some ways hearkens back to the aesthetic of the great German music of the Romantic era. (Perhaps Kraftwerk can be seen as a reflection of Ernst Jünger’s idea that the gods are being replaced by the Titans, who are returning to being in the form of our machines. There is certainly something almost religious about the way Kraftwerk pays homage to our mechanical creations.) It also marked Kraftwerk’s rejection of the usual subjects of pop songs, such as love affairs and angst, in favor of an optimistic view of the possibilities of the future and for our civilization. As such, Kraftwerk can be seen as quintessentially Faustian, daring to break free of the constraints of the old in favor of a world that has been reshaped according to the will of the creative and heroic mind.

“Autobahn” was an international hit and cemented Kraftwerk’s place as a band to which people were paying attention, both in the popular market as well as in the world of professional musicians. Indeed, Kraftwerk became one of those rare bands that managed to combine popular success with admiration even among the denizens of high-art criticism. In addition to the title track, however, Autobahn contains four other songs which are in the same style as their earlier albums, but which mark the end of what could be called their experimental period.

Autobahn also saw the coming together of the personnel lineup that would remain consistent throughout Kraftwerk’s glory years. During the first phase of the band’s existence, apart from Hütter and Schneider, the musicians who made up the band had been constantly changing, with many people coming and going (several of whom went on to be successful musicians in the Krautrock scene in their own right). The production of Autobahn saw the introduction of Wolfgang Flür, a drummer, to the group, and Karl Bartos, also a percussionist, joined them for their Autobahn tour in 1975 and ended up staying. These four were to remain the consistent faces of Kraftwerk for the next twelve years, and they are still the ones most readily recognized as the group’s core. In spite of this, Kraftwerk was unusual in that, from its origins up to the present, its members have always shunned the spotlight, preferring to present themselves more as anonymous, robotic “musical workers” who are part of a collective rather than as individual personalities – again, something that Laibach was to emulate in later years. The members of Kraftwerk have seldom given interviews, and when they do, they rarely talk about their personal lives or their work habits, and even today little is known about Hütter and Schneider.

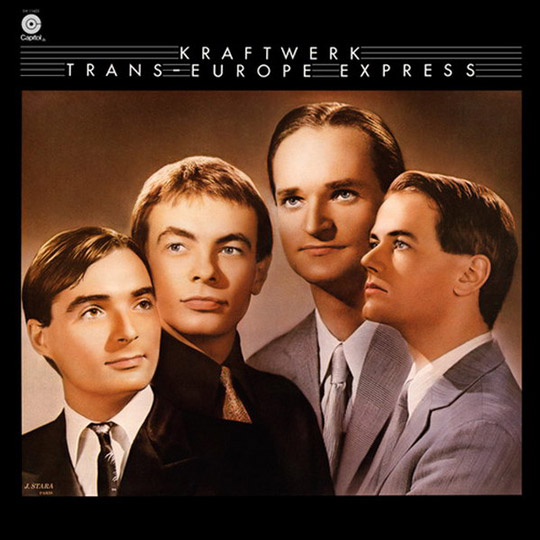

Also, after Autobahn, the band developed a highly conservative aesthetic in public appearances, donning suits and ties, which contrasted sharply with the look that had come to define popular music in the 1970s, when it was dominated primarily by long-haired, bearded hippies and punks sporting a more adolescent, in-your-face countercultural look that sought to defy convention. This is nowhere more apparent than in the cover art for Trans-Europe Express, which evinces an aesthetic that is more than just a bit “fashy”:

[13]

[13]This image was made using a photograph taken by J. Stara in Paris and then retouching it, apparently in order to make the band members look like mannequins.

Speaking of fash, unlike their Slovene spawn, Laibach, there are almost no instances of Kraftwerk making use of fascist imagery – which, even had they desired to do so, would have been impossible in 1970s Germany in any event. Although there is one exception worth noting: the original album cover of Radio-Activity featured a drawing of a Volksempfänger, or “people’s receiver,” which was a radio developed by Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda for mass production and then distributed by the millions to the German people. I hesitate to read too much into this, given that it remains the only instance in Kraftwerk’s entire body of work of their use of a fascist image, and it is a very ambiguous one at that – but they did “go there” at least once.

[15]

[15]Kraftwerk’s aesthetic very much plays into the fact that the band was the first distinctively German group to achieve international success since the Second World War. Within Germany, critics have said that German listeners of the 1970s were very keenly aware of the fact that Kraftwerk’s style was a subtle mockery of the vacuousness of schlager music, adding a layer of irony to their work that may not be readily apparent to outsiders.

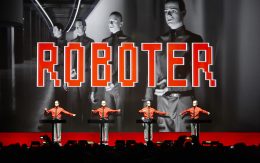

Additionally, Kraftwerk were also surely aware of their international audience’s conception of Germans in terms of the clichés about them being emotionless, anal, workaholic, and of course, Nazi. Rather than seeking to undermine these assumptions, Kraftwerk decided to take them to the furthest extreme, presenting themselves as some sort of synthesis between men and machines uninterested in the trivialities with which most pop music is concerned. Indeed, the highlight of any Kraftwerk concert has long been “The Robots,” which features the repeating line, “We are the robots,” when the band members themselves leave the stage and are replaced by actual lookalike robots that move in time to the music (in effect being more physically demonstrative than the human band members often are on stage). This is further underscored by their classic ending to their live shows, “Music Non-Stop,” during which each of the four members one by one waves goodbye and leaves the stage until no one is left, and yet the music continues to play, with each layer of the music gradually breaking off until all that can be heard is the vocoder repeating “music non-stop.” In both instances, the audience is invited to ask how much of Kraftwerk is human and how much is machine-generated.

Kraftwerk was also unique in the 1970s for creating a particularly German aesthetic, which included singing most of their songs in their own language rather than in English, as was the custom at the time (even though most of their songs have always been rerecorded in various European languages for the international markets). As such, in addition to being trailblazers in the musical world, they should also be seen as a watershed in the reemergence of a genuine and distinct German culture in the wake of the Second World War.

Kraftwerk had now hit their stride, and they released five more albums in quick succession over the eleven years following Autobahn: Radio-Activity [17] (1975), Trans-Europe Express [18] (1977), The Man-Machine [19] (1978), Computer World [20] (1981), and Electric Café [21] (1986), the latter renamed in subsequent years as Techno Pop. Also notable during this period was their single Tour De France [22], released in 1983, which went on to become an integral part of the group’s oeuvre in spite of the fact that it was not included on any of their proper albums until it appeared, in several different versions, on 2003’s Tour De France Soundtracks.

Radio-Activity is perhaps not as widely regarded as their other albums from this period, but it nevertheless marks the final transition from the group’s early, psychedelic, and experimental style to their later, much more polished sound. It also showed Kraftwerk’s growing concern with having a theme for each album around which each song would revolve. All of the songs on Radio-Activity pertain in some way to the theme suggested by the album’s title, featuring lyrics and motifs relating to nuclear energy and radio waves.

Trans-Europe Express, my personal favorite, depicts a journey along the railway of the same name, which was an actual rail service that operated in Europe from 1957 until 1995, featuring rhythms and sounds describing a train in motion. And, as the title suggests, while all of Kraftwerk’s music is strongly European in tone, there is something quintessentially European about its songs. It was the first of their truly “danceable” albums, and exerted a great deal of influence on dance music at the time. The album also includes “Showroom Dummies,” about some dummies that come to life, escape from their store window, and go to a club to dance, which presages Kraftwerk’s later fascination with robots replacing humans. The album concludes with two instrumental songs that run into one another, “Franz Schubert” and “Endless Endless,” their two best instrumental songs of all in my opinion, which always evoke in my mind a coastal European city, bathed in the twilight of sunset just giving way to night. But the first song on the album, “Europe Endless [23],” is my absolute favorite among all of Kraftwerk’s work (and it was apparently the entire album’s working title), and in my opinion deserves to become the anthem of Europe in the place of the butchering of the fourth movement of Beethoven’s Ninth that currently holds that title. Its literal meaning, of course, could be seen as describing the endless landscape of Europe as it flows past the windows of a moving train. But for me it has much deeper significance. While listening to it I can always envision a European landscape, cities and towns and countryside streaming beneath my imaginary eye as the various elements of which Europe is comprised flow on forever and blend together, across both time and space. One of its few, simple lyrics seems to emphasize this: “Life is timeless,” to me suggesting the timelessness of the life of Europe as a civilization, with all of its sundry activities, good and bad, personal and world-historical, throughout time. The music likewise evokes Europe as an endless dance through the ages, with many faces coming and going but the line of our people always remaining constant through all their various trials, giving the impression of something evolving and changing, but never ending, and always looping back around toward its origins to begin anew. Two of the other lyrics also seem to capture something of the essence of the contemporary European reality: “real life and postcard views,” which to me describes the dichotomy between Europe as something relegated to a gigantic museum of our ancestors’ legacy and its natural beauty, with almost too much care having gone into its nonetheless stunning presentation, and Europe as a living entity today, with an evolving destiny; and also “elegance and decadence,” which minimalistically captures the two poles that are constantly tugging modern Europe in two different directions. And endless has another meaning, too, if one can imagine the idea of “Europe Endless” as describing the endless flow of our people through history, enabling us to see ourselves at this present moment as only part of a stream extending back into the mist-shrouded past of our ancestors and extending onward into an as-yet-invisible future across those lands which have always been, and always will be, our people’s home. Listening to this album never fails to move me.

Kraftwerk’s next two albums, The Man-Machine and Computer World, venture beyond contemporary inventions and into the world of science fiction, depicting technologies that were just being developed at the time or else that were destined to come into existence in the near future. The eponymous track from their former album became one of Kraftwerk’s signature tunes, and, along with “The Man-Machine” from the same album, depicts a world where robots and cyborgs have become commonplace. It also features “Spacelab,” anticipating the International Space Station. Computer World’s eponymous song foretold the rise of the Internet, while “Computer Love” prophesied online dating sites; “Home Computer” describes the wonders of the personal computer, which was just on the cusp of exploding into the mainstream and altering civilization forever when the album first appeared.

The last of Kraftwerk’s major albums, Electric Café, isn’t as groundbreaking as their earlier albums, and doesn’t really have a clear unifying theme like their previous few, perhaps betraying the fact that the band was coming to the end of their richest creative juices, but it nevertheless remains a fun album to hear, especially “The Telephone Call [24],” for which they made my favorite – and most Teutonic, in my view – video of theirs.

The interesting thing about Kraftwerk during its renaissance was that it offered paeans to technology, both contemporary and futuristic; but quite often, the technology being described wasn’t as those at the time might have envisioned it, but as it might have been imagined in the 1930s, ’40s, or ’50s. This becomes particularly obvious in their album art, videos, and the backdrops they have used in their concerts – the projections for “The Model,” from The Man-Machine, for instance, makes use of old black-and-white footage of European fashion models from the mid-twentieth century. Likewise “Metropolis,” also from The Man-Machine, which brings to mind the classic Fritz Lang silent film of the same name from 1927, and indeed, even the music itself seems to evoke a type of chrome-and-biplanes city rather than, say, present-day New York. And even in those instances where technology has caught up with Kraftwerk – as with, for example, the personal computer – the images they continue to use in their shows are nevertheless those of computers from the 1980s, so what one has now is a futuristic device as imagined by artists from the 1970s and early ’80s imagining what things would be like in the twenty-first century, now being presented nostalgically by artists in the twenty-first century. Ample fodder for any postmodernist critic, to be sure.

From a Right-wing perspective, however, Kraftwerk has appeal given its implicitly “white,” European, and conservative aesthetic. As previously mentioned, the band had eschewed the conventions of their time by going with suits and ties; in addition to this, all of the subjects, languages, and imagery that Kraftwerk have made use of over the years, with very few exceptions (a few references to Japanese is all I can think of at the moment), is very specifically and exclusively European. During their recent concert in Budapest, this was brought home for me by the video backdrop used for “Tour de France,” which featured black-and-white footage of the bicycle race – in itself an implicitly European sport – taken from sometime in the mid-twentieth century, and with lyrics only in French, even on the international releases. This reminder of a better time in European history, when the Tour de France was an event by Europeans, for Europeans, without the need for token minorities on display, is at sharp variance with what one finds depicted elsewhere in popular culture.

After Electric Café, however, began a long period of silence. Since 1969, the group had never gone more than three years without releasing new material, but after 1986, it wasn’t until 2003’s Tour de France Soundtracks that Kraftwerk offered any original material whatsoever. And now, more than thirty years on from Electric Café, very little has changed. Warning signs had already made themselves apparent. In 1987, the first of their classic lineup, Wolfgang Flür, left the band, an ominous sign; and he was soon followed by Karl Bartos in 1990. The two were rumored to have left in frustration with the band’s lack of productivity and its founders’ increasing perfectionism. In 1991, Kraftwerk released The Mix, which was an attempt to update their greatest hits for the digital age by taking into account adjustments they had made in their live shows since the original albums had first come out, but it contained no new material. When I initially became interested in them in the mid-1990s, fans were still confident that they were just in the midst of a prolonged break. And when they went on a US tour in 1998 – their first since 1981 – and performed three new, if not particularly impressive, songs as part of their set (they sounded more like the beginnings of songs than finished products), many people took this as an indication that a new album was imminent.

But the years continued to pass, and nothing new was forthcoming. In 2003 they released the aforementioned Tour de France Soundtracks to commemorate the centenary of the event, which reflected Hütter’s obsession with cycling. In addition to four different versions of the title song, which dated from 1983, the album did indeed feature seven new tracks – which were welcome, to be sure, and which were good, but none of them approached Kraftwerk’s earlier work for power, innovation, and appeal. And even that album is now fifteen years old. Since then, only two more albums have appeared, both of which consist entirely of new performances of their classic hits: Minimum-Maximum (2005) and 3-D The Catalogue (2017), the latter of which is taken from their current tour. And as if to hammer home the idea that Kraftwerk as a living force is now relegated to history, Florian Schneider himself left the band in 2008, leaving Hütter as the only one of the members from the group’s golden years to remain.

So it seems that, barring unforeseen surprises, Kraftwerk has given up trying to create new material. Music critics have been speculating for decades about why this is. Most agree that it was probably the result of the difficulty they were having in remaining on the cutting edge of a field that they pioneered, but which quickly became populated by many other groups doing similar things who, ironically, were in many cases largely inspired by them. Kraftwerk basically created techno as a genre, and also contributed toward the development of ambient, industrial, disco, hip hop, dance music, and rock, as well as experimental electronica. And even now, more than thirty years since their best-known songs were released, you can still hear the influence of, and sometimes even samples from, their music in some of the latest tunes across many genres.

But in spite of the paucity of fresh music, Kraftwerk has not been entirely idle, instead choosing to focus on developing their performance style. They have continued to tour regularly, as they are presently doing, and after not having seen them for nearly thirteen years, I was curious to see what was new.

Since 2013, Kraftwerk has been touring what they call their “3-D The Catalogue” show – and it premiered at no less a venue than the Tate Modern in London – which refers to the fact that the animations that are being projected behind them during the performance are now 3D, and each member of the audience is issued 3D glasses upon entering the venue. The online announcements of the show touted that this new style of performance was a true Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total work of art” representing all the various branches of art working in harmony together, a concept first coined by Wagner to describe his own music-dramas. One could certainly argue that Kraftwerk’s music has always been a type of Gesamtkunstwerk. But based on what I saw in Budapest, I’d have to say that the 3D aspect is just about the only new aspect of their performance. Basically everything else, from the songs they played, to the sound of the songs, to the order they were played in, was exactly the same as I remembered from their Detroit concerts in 1998 and 2005, apart from the fact that the three “in progress” songs they had played in 1998 had been replaced by three of their newer tracks from Tour de France Soundtracks.

The atmosphere of the show was very different as well. The two concerts I saw in Detroit had open seating (or, more correctly, standing), and some people were dancing – which should be expected given this type of music. In Budapest, however, the impression one had was more of a classical music recital – seating was assigned, and there were actual seats arranged across the span of the enormous Budapest Arena that one was expected to remain in for the duration of the performance. (I am pleased to report that it was a nearly sold-out crowd, in spite of the large space.) In Detroit in 1998 and 2005, the audience had been able to come up to the stage, which was an essential feature for the performance of “Pocket Calculator” from Computer World, when, traditionally, the band members would take out an actual device that they would pass to people in front of the stage so that they could play the “little melody” featured in the song, something which was a great crowd-pleaser. There was no calculator in this show, however – there was a wide gap between the band and the audience on this occasion. While the mood was certainly very different, perhaps there is something fitting in this, reflecting that Kraftwerk is now more akin to classical than it is to pop music, being that it has grown to be more for connoisseurs than for those just out looking for a good time. I certainly noticed that a large part of the audience, including me, was over forty – probably reflective of the fact that many younger people have never heard of them.

As an aside, I’ll just mention that I still find their performance of 1976’s “Radioactivity,” from the album of the same name, somewhat grating. Along with their impersonal presentation style, Kraftwerk has always been doggedly apolitical – with one exception. In 1992, they chose to perform at a “Stop Sellafield” concert festival in England, which was a protest against the nuclear power plant in Sellafield, which had the distinction of being the first nuclear plant to operate on an industrial scale, becoming operational in 1954. To suit the needs of the occasion, Kraftwerk chose to modify “Radioactivity” so that it opened with their famous vocoder making a stilted announcement about the amount of radioactivity that was being released into the atmosphere by the plant. During the song itself, they further modified its famous lyric, “Radioactivity is in the air for you and me” – a typically delightful, ambiguous, tongue-in-cheek quip that is characteristic of Kraftwerk’s lyrics, where you don’t know if they’re being serious or not – by clumsily inserting “STOP” before every instance of the line. They further added a line reciting a list of nuclear plants that had suffered accidents, to which in recent years they’ve added “Fukushima,” and some lyrics in Japanese as well. This is the version that they have toured with ever since 1992. Here is not the place to debate the merits of nuclear energy, but in any event, I’ve always found the modified version annoying simply because it is so out of character for the band to break their usual impassiveness in such a blatant and unartistic way. I suppose, like many superstars, they developed a guilty conscience. I was at least relieved that they have now removed the vocoder bit at the beginning, probably because Sellafield is now in the process of being decommissioned.

There were some differences from 1998, however. One is that the band members now sport black, skintight bodysuits covered in lines of LED lights, as opposed to the dark suits of old. Kraftwerk stood impassively at their consoles throughout the performance, barely registering any reaction that I could see from where I was sitting, although the LED lights served to highlight their legs and feet as they tapped in time to the music. Kraftwerk has never been known for being particularly emotive stage performances, but still, in 1998 I remember them showing some emotional reactions, and they were clearly enjoying themselves and dancing during “Pocket Calculator,” when they also would interact with the audience. There was none of that this time around, something which even former member Wolfgang Flür commented on in a critical review [25] of their current show, writing, “We used to move; these robots don’t.”

But the main difference, of course, was in the animations. Several of them seemed identical to what I remembered from 1998 and 2005, but several were certainly new, and the 3D element was put to good use in them. “Autobahn,” in particular, in which the journey down the road was depicted [26] using graphics consistent with the original 1974 album cover, was quite impressive, as were the images [27] which accompanied “Spacelab,” which showed us an orbiting space station in rich detail, as well as a UFO landing just outside the venue.

The music, as far as I could discern, was identical to what I remembered from Detroit. Since 1991 Kraftwerk has always used the revised versions of their songs from The Mix rather than the originals. The songs from The Man Machine, Computer World, Electric Café, and Autobahn all sound largely the same as the originals, although those from Radioactivity and Trans-Europe Express are considerably different – and not necessarily for the better, although that’s a matter of taste. I like the sound of 1970s electronica, so what might sound archaic to some is mellifluous to my ears. Hütter was never renown for his vocals, although his voice seems to be much the worse for wear these days, seeming to strain even to sing the few simple vocal lines that call for human voices – I couldn’t help but remember that he is now 71 years old, something easy to forget given that his figure in the bodysuit remains trim, no doubt due to all the cycling. There were also a few flubs in the instrumentals, especially in “The Man-Machine” – not enough to ruin the experience but sufficient to put to rest any doubts that everything in the show was either prerecorded or otherwise being produced automatically. At the end, I was thrilled that Hütter made his farewell during “Music Non-Stop” by saying “Auf Wiedersehen” – once again reminding the audience that Kraftwerk is, and could only be, German.

I don’t want to dwell too much on the negatives, however – I’m probably just jaded after following them for so many years. I had hoped to find more differences from their earlier performances, but even though there weren’t, it was still a thoroughly enjoyable experience – albeit more like seeing a great orchestra playing Beethoven’s Fifth for the umpteenth time rather than something new and exciting; still thrilling, even if you can anticipate every note. And perhaps it is fitting that, for a band as conservative in its concept as Kraftwerk, they should likewise be conservative in how they choose to present themselves to the public and not indulge in change merely for its own sake. For someone who had never seen Kraftwerk live before, I’m sure it would have been an unforgettable experience, and I would certainly encourage anyone who has not seen Kraftwerk in concert to do so while they are still touring. Although given that Kraftwerk has always presented themselves as interchangeable and featureless workers, it’s entirely possible that once all the current members have retired that an entirely new lineup could keep the legend alive – and who knows? Maybe one day androids will tour in their place.

But as for me, as much as I was grateful to be able to see them one more time, I suppose I long for the good old days of the 1970s, when I could have gone to see Kraftwerk play in some small and dingy club in Germany, not as demigods of the musical world, but as something I was just discovering for the first time like a revelation, with all the imperfections the equipment they were just developing at the time would have added to their sound, and before they had had a chance to hone and perfect each song through ten thousand rehearsals and concerts. That adds yet another level to the postmodern Möbius strip of Kraftwerk’s aesthetics: I want to see a band from the 1970s, playing music that they made to anticipate the future, a future as seen through the lens of the earlier twentieth century, but all within the context of my twenty-first century existence. And I suppose there is nothing more Kraftwerkian than that.

Kraftwerk is a true manifestation of archeofuturism. And it serves as an example of how, by combining new ideas and technology with the aesthetics and values that have long defined our civilization, Europe can truly be endless.