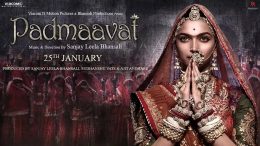

Padmaavat

Posted By Alex Graham On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,025 words

[1]Bollywood’s latest blockbuster release, Padmaavat, is based on the epic poem Padmavat, a fictionalized account of Alauddin Khalji’s conquest of Chittorgarh in 1303 written by a Sufi poet in the sixteenth century.

[1]Bollywood’s latest blockbuster release, Padmaavat, is based on the epic poem Padmavat, a fictionalized account of Alauddin Khalji’s conquest of Chittorgarh in 1303 written by a Sufi poet in the sixteenth century.

According to legend, Alauddin, ruler of the Delhi Sultanate, set out to conquer Chittorgarh upon hearing of the extraordinary beauty of Rani Padmini, or Padmavati, a queen married to Ratan Singh, the Rajput ruler of Mewar. When Chittorgarh fell after a prolonged siege, Padmavati and the other Rajput women committed jauhar (mass self-immolation), choosing death over dishonor.

The Rajputs (from the Sanskrit for “son of a king”) are a subset of the kshatriya caste generally concentrated in northern, western, and central India. Historically they were renowned for their martial prowess; the Rajputs were among the peoples that the British designated as “martial races.” To this day, many Rajputs take great pride in their warrior heritage.

The practice of jauhar originated among the Rajput kingdoms of northwest India and is somewhat analogous to the Japanese custom of seppuku. In the face of certain military defeat, Rajput women would immolate themselves en masse along with their valuables and finery in order to preserve their honor and evade being captured and raped by Muslim invaders. Dying a painful death by fire signaled that they killed themselves not out of fear but as an act of defiance.

The film met with violent opposition leading up to its release. Incensed by rumors that the film would feature relations between Padmavati and Alauddin, Hindu nationalist groups such as the Karni Sena staged violent protests throughout the country attempting to halt the production of the film, assaulted the director (Sanjay Leela Bhansali), vandalized film sets, and threatened to behead the lead actress.

It now appears that a faction of the Karmi Sena recently withdrew its opposition to the film and is now promoting it, according to the Times of India.[1] [2] Indeed, there are no scenes featuring Padmavati and Alauddin together beyond a brief scene in which he catches a glimpse of her face obscured behind a cloud of smoke, and the film extols the aristocratic warrior virtues of the Rajputs. Ratan Singh is portrayed as a stoic warrior and a wise ruler and Padmavati as a paragon of loyalty and courage. A Rajput is said to be one who “braves any situation,” “dares to walk on burning embers,” and “fights the enemy till the last breath.” Padmavati exhorts her people to “defend the pride of the motherland” and fearlessly leads the women of Chittorgarh to their deaths at the film’s dramatic climax. By contrast Alauddin (a hypnotic performance by Raveer Singh) is depraved, deceitful, and bloodthirsty almost to the point of caricature.

Another testament to Rajput valor occurs after Alauddin kidnaps Ratan (inviting him to his camp under the pretence of offering hospitality) and demands Padmavati in exchange for the king’s freedom. Padmavati agrees to the deal under the condition that her entourage of female servants would accompany her in 800 palanquins. As Padmavati escapes with Ratan through a secret tunnel, Rajput warriors led by Ratan’s brother Gora suddenly burst out from the palanquins and attack Alauddin’s men. They fight to the last man and Gora and his nephew Badan both die in battle.

Like Bhansali’s other films (Devdas [see Trevor Lynch’s review here [3]], Bajirao Mastani), Padmaavat is visually stunning and the cinematography is breathtaking. The film ranks as the most expensive Bollywood film ever produced, and the sets are opulent and grand, ranging from palatial interiors to vast battlefields. In the battle scenes the camera often alternates between being close to the ground, heightening the intensity of the action, and high above, panning across sweeping landscapes. The costumes are also highly ornate.

The visuals (enhanced by a 3D viewing) more than compensate for the characters’ relative one-sidedness and the occasionally lagging plot. (Oscar Wilde: “It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances.”) The film is really a pageant. There are a handful of musical numbers throughout the film, two of them featuring large-scale dances (Alauddin’s “Khalibali” and “Ghoomar,” a Rajasthani folk dance). The soundtrack overall is very effective and draws heavily from traditional Indian music.

The pageantry of the film is on full display in the scenes featuring court rituals and religious festivals such as Diwali and Holi. There are references to Hindu mythology throughout. Padmaavat is completely devoid of the irony, insincerity, and superciliousness that pervades Hollywood films, and Hindu traditions are portrayed with reverence and dignity.

Another stark contrast between Padmaavat and the average Hollywood film lies in its portrayal of sex/romance and male-female relations. The film is suffused with eroticism, but there are no overtly pornographic scenes. In place of ham-fisted lewdness, there are merely subtle gestures, such as Padmavati smearing Ratan’s face with saffron, a dimly lit shot of figures behind a curtain, etc. The film also honors traditional sex roles and it is taken for granted that men and women should inhabit separate realms in society. Padmavati is intelligent and strong-willed but does not demand “equality” or infringe upon her husband’s role as ruler of the kingdom.

Much of the controversy over this film surrounds the final scene, in which Padmavati and the other Rajput women commit jauhar. The film glorifies jauhar and extols Padmavati’s decision as an act of heroism. It is telling that feminists are offended by this: prizing self-preservation and bourgeois individualism above all else, most feminists would ultimately opt for a life of subjugation and sexual slavery over dying for higher principles if faced with the choice (one young modern Rajput woman states in the Huffington Post that in Padmavati’s position she would have “compromised and stayed with Khilji” to save her own skin).[2] [4]

Bollywood films are quite different from what most Westerners are accustomed to. Yet for all its exotic trappings, Padmaavat and the Aryan martial virtues it promotes are less alien to whites than the cultural rot pushed by the alien elite at the helm of Hollywood. It is also worth noting that the lead actors are relatively light-skinned and have European-looking facial features. Overall Padmaavat is a breath of fresh air and makes for an incredible viewing experience.

Notes

[1] [5] https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/entertainment/hindi/bollywood/news/karni-sena-faction-now-okay-with-padmaavat-release-in-rajasthan/articleshow/62764193.cms [6]

[2] [7] http://www.huffingtonpost.in/2018/01/24/for-these-rajput-women-padmavati-is-now-a-curse_a_23342945/ [8]