Neville & the Rebel:

Reflections on Colin Wilson & Neville Goddard

Posted By

James J. O'Meara

On

In

North American New Right

6,326 words

Part 1 of 2

“What was needed was not some new religious cult but some simple way of accessing religious or mystical experience, of the sort that must have been known to the monks and cathedral-builders of the Middle Ages.”–Colin Wilson[1] [2]

“The serpent said that every dream could be willed into creation by those strong enough to believe in it.”–Eve to Adam, in Shaw’s Back to Methuselah

Colin Wilson spent his life and his career–for him, as an existential philosopher, the two are one–pursuing a method, first in philosophy and literature, then in the occult, that would “crystallize into a philosophy of life that will bring order out of chaos and unity out of discord.”[2] [3] Can we say that another occult figure taught such a method before Wilson was even born? Most decidedly, we can![3] [4]

One of the most irritating tropes of our age–at least among the dominant SJW journalistic class–is the PC (Politically Convenient) Anecdote, in which the journo starts off by narrating some incident that just happened to them, or something they just happened to overhear, which constitutes a total validation of some supposed problem or assumption on their part, thus kicking off the essay or article exploring this continuing abuse crying out for immediate attention.

It seems particularly characteristic of the more social commentators, from Barack Obama, always with a handy story of his grandmother’s racial insensitivity, to the likes of Ta-Nehisi Coates, who can write entire books based on what some person (white, of course) supposedly muttered when Coates’ dawdling child backed up the crowd on an escalator.

What’s key is that the damning Anecdote is always Conveniently Private (or CP; like PC, get it?); or, if technically public, no recording or witness is around for later verification, should some hateful fascist demand such. For example, after The Coming of Trump, tormented snowflakes tweeted and YouTubed endless stories like this one:

So, I was in line to vote, and these two guys behind me, real frat boy-looking, starting talking real loudly about how they were gonna get some ropes and take care of the immigrants. And I’m like, dudes, don’t you see I’m Hispanic, and everyone around you is too? And they just laughed and said “it’s Trump time, bitch!” I was never so scared in my life, but I voted anyway!

And for my part, I’m like, “Bullshit!” Two “frat boys” not only living in an overwhelmingly Hispanic voting district, but they’re taking the opportunity, while standing in line, no doubt next to some cops and voting overseers, to rant about lynching immigrants. Yeah, that happens.

Although this is obviously rampant in the Current Year tsunami of rape accusations and hate hoaxes, it occurs on smaller scales throughout our sorry culture. And I was reminded of it when Phil Baker, attempting to convey the deep loathing of the British literary establishment (yes, there still is such a thing, or at least something that thinks it is) for the late Colin Wilson, produced this supposed anecdote:

Meanwhile Iain Sinclair, master of the ambulant put-down, has been less restrained. Walking round a book market in his semi-autobiographical novel White Chappell Scarlet Tracings, he notices a haggler “beating down some tattered Colin Wilsons from 20p to 5p: unsuccessfully. Overpriced at nothing.”[4] [5]

Yeah, I know, it’s a novel, but it’s “his semi-autobiographical novel,” meaning it has a claim to a footing in reality; he’s not leaping over a tall building, or plotting 9/11. The anecdote is supposed to be actual, or at least leave the reader with the impression, like a Russian novelist, that “the like of this happens nowadays.” Or as Trollope would say, “The Way We Live Now.”[5] [6]

It’s the purest expression of PC dogma, offered, perversely, as evidence therefor.

And indeed, Baker’s “review” is just another opportunity for an establishment Insider (which is even to use Wilson’s own terms) to put the boot in to the man who, ironically enough, seems to have replaced Aleister Crowley as “The Most Evil Man in Britain.”[6] [7]

Towards the end of his non-stop smirk-sneer-and-smug-fest, Baker lets drop a very significant insult (it’s not relevant enough to call a ‘point’): Lachman’s publisher blurbs that they “also publish Napoleon Hill’s Think and Grow Rich.” My God, the jumped up little pseudes! And proud enough of it to put it on the cover, too![7] [8]

This, a more specific version of his querulous complaints about Wilson being popular among those American colonials, establishes a tenuous connection between Wilson and New Thought. And this accusation leaves my withers–whatever they are [9]–unwrung. For as Constant Readers know, I’ve long been thumping the drum for what I call our native-born Neoplatonism, our home-grown Hermeticism, our two-fisted Traditionalism.

And although it would be too much to expect that Baker has any more respect for those traditions–he strikes me as the kind of pretentious parlor pinko who mocks parapsychology but adheres to some kind of “science”-based progressivism–they are definitely European.[8] [10]

On the other hand, it may not matter much, whether we insist on Neville and New Thought in general being colonial outbreaks of the Western (European) Tradition–in Spengler’s terms, a “second religiosity” characteristic of senescent cultures; or as the birth of the spirituality of a new cultural cycle in the New World.[9] [11] Surely what matters is: it works!

Or is that oh so American an attitude? Fine; we’ll leave our epicene cousins to their thrilling games of U and Non-U and other One-upmanship,[10] [12] and get on with the task of living. And that, of course, was Colin Wilson’s greatest sin: taking life seriously.

It’s a synecdoche of Wilson’s problematic, shall we say, reputation that while The Outsider has been more or less in print since 1956, his second book, Religion and the Rebel, has been out of print for 27 years. However, the end of 2017 brings news that Aristeia Press of London are bringing out a new edition (with an “Historical Introduction” by ubiquitous Wilsonian Gary Lachman).

As famous and as oft-told as the story of Wilson’s overnight fame after The Outsider is, just as famous and oft-told is the second act, the universal hatred, contempt and loathing that greeted its follow-up, Religion and the Rebel. Without rehearsing all that, it’s clear, to me at least, that Wilson’s own account[11] [13] (despite what must be some amount of bias and self-interest) is fundamentally correct. While one might expect his sophomore effort (an all-to appropriate word in his critics’ opinion) to fall below the standard of the first, or to fail in its perhaps overambitious goals, the wholesale revision of Wilson’s reputation from genius to fraud, from earnest if not angry young man to charlatan, often announced by the very same critics, is impossible to justify.

Religion and the Rebel is clearly the sequel, or continuation, of The Outsider, advancing its concerns and maintaining the same high level. The vociferous negative response, and Wilson’s subsequent banishment from “serious” discourse, can only be explained as one of those all too typical changes in critical fashion, where a book, say, is picked up and relentlessly promoted by Those Who Know, and then the author’s next book is the occasion for an equally relentless thrashing, after which the author is forgotten and a new one selected to repeat the process.[12] [14]

Counter-Currents readers are well acquainted with the Cathedral and the Megaphone,[13] [15] and if not already fans of Wilson can be assumed ready to give him a fair shot–the enemy of one’s enemy, after all.

I assume a certain basic familiarity with Wilson and especially his first and most famous book, The Outsider, on the part of any reader of Counter-Currents–because what more of an Outsider type could there be than such a one? If not, I can refer you to John Morgan’s excellent piece on this very website–”A Heroic Vision for Our Time: The Life & Ideas of Colin Wilson” (here [16]), as well as a review by Sir Oswald Mosley (here [17]).

Tom X. Hart provides a nice summary of the arc of Wilson’s thought, which oddly enough seems easier to see by moving backwards, and has the advantage of tying in many of the strands, especially the political:

Wilson’s philosophy can be divided as follows:

- Human beings have a hidden potential, Faculty X, which once fully realised will allow humans to greatly augment their powers, and possibly transcend death itself;

- An aspect of Faculty X is manifested in the ‘peak experience’, a term Wilson borrowed from the psychologist Abraham Maslow. The peak experience is, in essence, the ego destruction that is associated with meditation, sex, and near-death experiences. A person can obtain a peak experience through intense concentration on an object or thought. When the person shifts their attention from concentration an ecstatic moment follows as the person returns from a state where their ego is temporarily suspended;

- There have been people through history who have attained or understood Faculty X. These include extraordinary figures such as TE Lawrence and Van Gogh — as well as more marginal figures, such George Gurdjieff and Rasputin;

- Faculty X and its associated properties may be involved in many ‘unexplained’, occult, or mysterious events through history. These include UFO sightings, Jack the Ripper, and other elements connected to the supernatural. Phenomenon that are discarded as pseudo-science, such as telepathy and synchronicity, are manifestations of hidden human potential;[14] [18]

- The existentialists and atheistic philosophers are depressing, and lack optimism in their materialist conception of man without God. There are grounds for optimism, and there is a possibility for human improvement — if only we have the will to find it. In this respect, Wilson echoes 19th Century optimism rather than 20th Century despair. The world can — will — get better. This salvation will be partly scientific. In this he resembles the 19th Century psychical researchers who thought that a scientific method would uncover evidence for the existence of an afterlife, and that communication with that afterlife would be possible.

What this philosophy represents is a hierarchical, optimistic, and occult approach to life that contains an implicit authoritarian politics.

His optimism tips the implicitly rightist ideas in his work towards fascism. Far-right ideas are not simply conservative in nature, but revolutionary conservative ideas. This not a glum defence of the old order. And revolutionaries must be optimistic about the world to come, if not their chances of achieving that world.[15] [19]

Quite an intellectual achievement for one man’s life! For our purposes, I want to concentrate on the earliest part of his thinking, as developed in the newly republished Religion and the Rebel, and draw out some comparisons with our favorite New Thinker, Neville Goddard.

Neville likes to present his teaching in the mode of commentaries on the famous “I Am” (or as he prefers to put it, “I AM”) sayings of the Bible–”I AM the Way,” “Before Abraham was I AM,” etc. One might well put together a similar set of Wilson’s pronouncements on the nature of The Outsider:

“The Outsider is a symptom of civilization’s decline; Outsiders appear like pimples on a dying civilization.”

“The Outsider’s final problem is to become a visionary.”

“The Outsider must raise the banner of a new existentialism.”

“The Outsider is the man who has faced chaos. The Insider is the man who blinds himself to it.”

“The Outsider must find a direction and commit himself to it, not lie moping about the meaninglessness of the world.”

“The Outsider cannot help feeling that men do not learn from experience — not the really important things.”

Interesting, but what does all this mean? Wilson considers Rebel to be an extension of the ideas discussed in The Outsider,[16] [20] and it is, but in two directions; reading it is rather like watching The Godfather Part II, in that it takes up the story both before and–in this case, speculatively–after the first book.

Schematically, it looks like this:

Rise of civilizations — Decline of civilizations and appearance of the Outsider[17] [21]–Renewal(?)

The middle part is largely covered by The Outsider, while Rebel takes up the before and after. I say largely, because the nature of Wilson’s method, what he calls the existential method, is to develop his ideas by examining–sometimes at great length–the way ideas have come to be worked out in the lives of great men–the Outsiders–and in his own life.[18] [22]

Colin Stanley says Wilson feels

The need to demonstrate that his philosophy is not just words on paper but ideas that can and should be proved by living. Personal anecdote becomes an integral part of his message, making it accessible to his audience.[19] [23]

And so there is some overlap as Rebel continues this method; for example, the discussion of possible civilizational renewal takes place largely in terms of another long (overlong, for this reader) discussion of Shaw’s career; adding as well three Wilson-centric introductions, an “Autobiographical” one, a “Retrospective” one from a later printing, and a “Historical” one by Gary Lachman for this edition.[20] [24]

Already we can see a parallel with Neville, who presents his teachings almost exclusively through personal anecdote and, especially as his audiences grew, the stories told or written to him by his (successful, of course) listeners.[21] [25] Like Wilson, as we’ll see, he had no interest in religious dogma or philosophical theory, insisting that everything he said had been proven in his own experience, and simply asking his listeners to go and do likewise.

Public opinion will not long endure a theory which does not work in practice. Today, probably more than ever before, man demands proof of the truth of even his highest ideal. For ultimate satisfaction man must find a principle which is for him a way of life, a principle which he can experience as true….

Having laid the foundation that a change of consciousness is essential to bring about any change of expression, this book explains to the reader a dozen different ways to bring about such a change of consciousness.

This is a realistic and constructive principle that works. The revelation it contains, if applied, will set you free.[22] [26]

At times, the aim to be practical even supersedes the testimonial method:

Were it possible to carry conviction to another by means of reasoned arguments and detailed instances, this book would be many times its size. It is seldom possible, however, to do so by means of written statements or arguments since to the suspended judgment it always seems plausible to say that the author was dishonest or deluded, and, therefore, his evidence was tainted. Consequently, I have purposely omitted all arguments and testimonials, and simply challenge the open-minded reader to practice the law of consciousness as revealed in this book. Personal success will prove far more convincing than all the books that could be written on the subject.[23] [27]

For our purposes, I am going to follow the latter method, and try to pull out what Wilson says on various–related–topics in order to compare them with Neville, especially his “simple method for changing the future.”

And in the spirit of Wilson’s existentialism, perhaps I could begin with some biographical comparisons.

First, Wilson was a product of the pre-War British working class–no doubt the basic root of the animosity directed at him by his “betters” among the chattering classes.

Neville, while born into a large, not particularly wealthy family in the British colony of Barbados (he likes to tell a story about the correct way to feel ducks for dinner, as he did as a child, and how it relates to our “mental diets”), they did eventually become–due, Neville insists, on father and brothers making use of his own imaginal methods–the proprietors of a chain of grocery stores which ultimately became, under the name Goddard Enterprises, the largest conglomerate based in the Caribbean.[24] [28]

Nevertheless, Neville, like Wilson, never received much job-related training and struck out early for the big city–New York, in his case–and lived hand to mouth at menial jobs until achieving some success as a dancer, ultimately starring in several Broadway shows.

Despite his success, he later said that the income of any one year was wiped out in a few months the next, and then the Depression put everyone out of work. However, as Israel Regardie pointed out, Neville’s natural aptitude and professional training as a dancer formed a crucial part in the method he taught; a point to which we shall return.[25] [29]

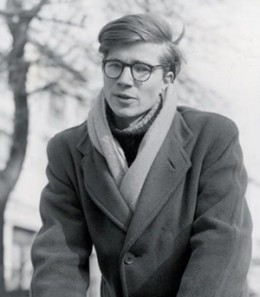

In addition, Neville was tall, handsome, and spoke with the sort of exotic accent Americans just love;[26] [30] he was made for the lecture stage. Wilson, though a fashionable enough Angry Young Man in his turtleneck jumper and RAF-issued hornrims,[27] [31] was never particularly charismatic on stage, at least in my experience.[28] [32]

Wilson the existentialist would agree, I think, that all this has an impact on their ideas; at least, it made it inevitable that Neville flourished on the lecture circuit, Wilson in books. And here again, things conspired against Wilson. Productivity in books is looked down on, again, by the Establishment.[29] [33]

Although Neville lectured constantly, he wrote only a handful of small books–booklets, really–which he never copyrighted; the contents of which, along with recordings of the lectures–again, freely made–fill the internets. And again, Wilson could hardly afford to eschew copyright, as much of his productivity was necessary to support his family.[30] [34]

And the topics! Parapsychology, sure, but Atlantis,[31] [35] pyramids, alien abductions… for Christ’s sake, Bigfoot? Not that there’s anything wrong with all that–for Feyerabend reasons,[32] [36] I think fringe areas are the most worthy of investigation–but it’s hardly likely to help your reputation.[33] [37]

After this dip into biography, let’s shift our focus back to ideas. The upshot of Wilson’s exploration of his selected Outsiders, against the theoretical background provided in Religion and the Rebel by Spengler and Toynbee, could be put this way:

Religion is the glue that holds society together; more importantly, from the Outsider’s perspective, it provides a refuge for the world at large, and a method or discipline to provide for the meaning of life missing from the secular world.[34] [38] It does so by providing a means, a method, of disciplining the will and the imagination so that the Outsider can fulfill his destiny and become a visionary.[35] [39]

As Wilson proceeds through the “Outsider Cycle” of books, the topic becomes more and more clearly a search for a method, as Sartre might say. While Sartre moved from existentialism to Maoism, Wilson wants to move from Sartre’s pessimistic existentialism to his own, optimistic version, “the New Existentialism.” Wilson’s optimism arises from the Shavian insight that The Outsider represents an evolutionary advance of consciousness; or rather, it would, if only a method could be found.

Method for what? In Religion and the Rebel, Wilson says that the inspiration for The Outsider was William James’ Varieties of Religious Experience, and goes on to combine James with Whitehead’s concept of “prehension,” a primal form of consciousness (or, in Husserl’s language, ‘intentionality’) that permeates organic life:

[James’s] argument amounts to this: Man is at his most complete when his imagination is at its most intense. Imagination is the power of prehension; without it, man would be an imbecile, without memory, without forethought, without power of interpreting what he sees and feels. The higher the form of life, the greater its power of prehension; and in man, prehension becomes a conscious faculty, which can be labelled imagination. If life is to advance yet a stage higher, beyond the ape, beyond man the toiler or even man the artist, it will be through a further development of the power of prehension. This craving for greater intensity of imagination is the religious appetite. (Loc. 6636-38)

The “conscious faculty” which satisfies the “craving for greater intensity of imagination” and thus solves the Outsider’s problem, is what Wilson will explore, as “Faculty X,” in his subsequent “Occult Cycle.”[36] [40]

Having brought in the notions of conscious control, imagination, and the occult, we can usefully circle back to compare these ideas to the teachings of Neville. Let’s start with a rather long quote from his very first book, At Your Command;[37] [41] patience will be rewarded.

Now let me instruct you in the art of fishing. It is recorded that the disciples fished all night and caught nothing. Then Jesus came upon the scene and told them to cast their nets in once more, into the same waters that only a moment before were barren–and this time their nets were bursting with the catch.[38] [42]

This story is taking place in the world today right within you, the reader. For you have within you all the elements necessary to go fishing. But until you find that Jesus Christ, (your awareness) is Lord, you will fish, as did these disciples, in the night of human darkness.[39] [43] That is, you will fish for THINGS thinking things to be real and will fish with the human bait–which is a struggle and an effort–trying to make contact with this one and that one: trying to coerce this being or the other being; and all such effort will be in vain. But when you discover your awareness of being to be Christ Jesus you will let him direct your fishing. And you will fish in consciousness for the things that you desire. For your desire–will be the fish that you will catch, because your consciousness is the only living reality you will fish in the deep waters of consciousness.

If you would catch that which is beyond your present capacity you must launch out into deeper waters, for, within your present consciousness such fish or desires cannot swim. To launch out into deeper waters, you leave behind you all that is now your present problem, or limitation, by taking your ATTENTION AWAY from it. Turn your back completely upon every problem and limitation that you now possess.

Dwell upon just being by saying, “I AM,” “I AM,” “I AM,” to yourself. Continue to declare to yourself that you just are. Do not condition this declaration, just continue to FEEL yourself to be and without warning you will find yourself slipping the anchor that tied you to the shallow of your problems and moving out into the deep.

This is usually accompanied with the feeling of expansion. You will FEEL yourself expand as though you were actually growing. Don’t be afraid, for courage is necessary. You are not going to die to anything by your former limitations, but they are going to die as you move away from them, for they live only in your consciousness. In this deep or expanded consciousness you will find yourself to be a power that you had never dreamt of before.

The things desired before you shoved off from the shores of limitation are the fish you are going to catch in this deep. Because you have lost all consciousness of your problems and barriers, it is now the easiest thing in the world to FEEL yourself to be one with the things desired.

Because I AM (your consciousness) is the resurrection and the life, you must attach this resurrecting power that you are to the thing desired if you would make it appear and live in your world. Now you begin to assume the nature of the thing desired by feeling, “I AM wealthy”; “I AM free”; “I AM strong.” When these ‘FEELS’ are fixed within yourself, your formless being will take upon itself the forms of the things felt. You become ‘crucified’ upon the feelings of wealth, freedom, and strength.–Remain buried in the stillness of these convictions. Then, as a thief in the night and when you least expect it, these qualities will be resurrected in your world as living realities.[40] [44]

I think it’s good to get the flavor of Neville thinking; but more succinctly, his “mechanism of creation” can be outlined thus:

- Formulate a definite desire, an obsession, and then imagine a dramatic scene that would be consequent of your desire being fulfilled, clearly articulated in every detail.

- Induce a state of total relaxation, a “state akin to sleep.”

- In this state, rise in consciousness until you are aware of yourself only as pure existence — “I AM” — without and before any definite determination, such as “I AM this or that.”

- Turn your attention to the preconceived drama, and hold it in your imagination until you intensely feel the emotion consequent to having attained your desire.

Reading this, one is immediately reminded of the central chapter of The Outsider, where Wilson, having concluded that “the Outsider problem is essentially a living problem [and] beyond a certain point, the Outsider’s problems will not submit to mere thought, they must be lived,”[41] [45] proceeds to examine the lives of three types of Outsider: the intellectual (T. E. Lawrence), the emotional (Van Gogh) and the physical (Nijinsky).[42] [46]

And, at the conclusion of Religion and the Rebel, Wilson reiterates the Outsider’s problem as:

Our civilization … is suffering from … too much intellect, and the consequent starvation of the emotional and physical factors. Existentialism is a protest on behalf of completeness, of balance [and] clearly plays the same role in the twentieth century that Christianity played in the Roman Empire in the first century … The solution … is for the individual Outsider to continue to bring new consciousness to birth.[43] [47]

Neville’s method is uniquely qualified to do so, as it addresses each of these factors. Schematically:

- Decide on a desired state, in great detail, ideally as a mini drama: intellectual

- Induce a state of relaxation akin to sleep: physical

- Feel the emotion consequent on the realization of this desired state: emotional

No wonder Neville lived a more successful life than Lawrence, Van Gogh, or Nijinsky, at least in existential terms. Neville is the ultimate existentialist, as Wilson understands the term. He has discovered and refined a method for rising in consciousness to the I AM (existence) that precedes any determinate form (essence), from which position I can chose any future state I desire.[44] [48] Remember all those “I AM” statements?

Unconditioned consciousness is God, the one and only reality. By unconditioned consciousness is meant a sense of awareness; a sense of knowing that I AM apart from knowing who I AM; the consciousness of being, divorced from that which I am conscious of being.

I AM aware of being man, but I need not be man to be aware of being. Before I became aware of being someone, I, unconditioned awareness, was aware of being, and this awareness does not depend upon being someone. I AM self-existent, unconditioned consciousness; I became aware of being someone; and I shall become aware of being someone other than this that I am now aware of being; but I AM eternally aware of being whether I am unconditioned formlessness or I am conditioned form.

As the conditioned state, I (man), might forget who I am, or where I am, but I cannot forget that I AM.

This knowing that I AM, this awareness of being, is the only reality.

This unconditioned consciousness, the I AM, is that knowing reality in whom all conditioned states–conceptions of myself–begin and end, but which ever remains the unknown knowing being when all the known ceases to be.

All that I have ever believed myself to be, all that I now believe myself to be, and all that I shall ever believe myself to be, are but attempts to know myself–the unknown, undefined reality.

This unknown knowing one, or unconditioned consciousness, is my true being, the one and only reality. I AM the unconditioned reality conditioned as that which I believe myself to be. I AM the believer limited by my beliefs, the knower defined by the known.

The world is my conditioned consciousness objectified. That which I feel and believe to be true of myself is now projected in space as my world. The world–my mirrored self–ever bears witness of the state of consciousness in which I live.

There is no chance or accident responsible for the things that happen to me or the environment in which I find myself. Nor is predestined fate the author of my fortunes or misfortunes. [45] [49]

This rising in consciousness and return also parallels Wilson’s discussion, via Toynbee, of the social role of religion and the Outsider, showing the connection between the social and personal aspects of the problem of the Outsider, which we will develop below.

Notes

[1] [50] The Angry Years: The Rise and Fall of the Angry Young Men (London: Robson Books, 2007; Kindle, 2014), p66.

[2] [51] Chap calling himself Zeteticus who conducted an online reading of Religion and the Rebel at the Soul Spelunker website; this is from Part Four, here: http://soulspelunker.com/2017/07/religion-rebel-part-4.html [52].

[3] [53] Neville, At Your Command (New York: Snellgrove Publications, 1939); see At Your Command: The First Classic Work by the Visionary Mystic Neville (Tarcher Cornerstone Editions, 2016), which includes Mitch Horowitz’s essay on Neville’s life and work, “Neville Goddard: A Cosmic Philosopher;” and see also my review here [54].

[4] [55] Phil Baker (TLS, Feb. 15, 2017) “Overpriced at Nothing: The Life and Work of Colin Wilson,” here [56]; reviewing Gary Lachman, Beyond the Robot: The Life and Work of Colin Wilson (New York: TarcherPerigee, 2017) and Colin Wilson, The Outsider (New York: TarcherPerigee, 2017; first published 1956).

[5] [57] For his part, Wilson himself says that “Second hand shops told me that certain people were obsessive collectors of my books, and would pay fairly high prices for them.” “The Outsider, Twenty Years On,” printed as the Introduction to The Outsider (New York: Diversion Books, 2014).

[6] [58] “Former home of ‘most evil man in Britain’ burns down,” The Telegraph, 23 December 2015, here [59]. Crowley is usually called “the Most Evil Man in the World”; is it not enough that his house should burn down, they have to put the boot in by demoting him? Or did Osama Bin Laden retire the title?

[7] [60] At least they don’t publish Savitri Devi . . .

[8] [61] See my “Magick for Housewives” in Aristokratia IV, as well as Mitch Horowitz’ One Simple Idea: How Positive Thinking Reshaped Modern Life (Crown: 2014).

[9] [62] Watts takes Spengler to task for not perceiving that great spiritual wisdom – such as Neoplatonism, Stoicism, and Christianity — not just New Age quackery, is found during these periods; and also speculates that the USA may not be part of the European old age but the birth of a new cycle.

[10] [63] “A battery of old grey men in club chairs, frozen in stony disapproval of this vulgar drunken American. When will the club steward arrive to eject the bounder so a gentleman can read his Times? … Old Sarge screams after them … ‘You Fabian Socialist vegetable peoples go back to your garden in Hampstead and release a hot-air balloon in defiance of a local ordinance. WE GOT ALL YOUR PANSY PICTURES AT ETON. YOU WANTA JACK OFF IN FRONT OF THE QUEEN WITH A CANDLE UP YOU ASS?’” William S. Burroughs, The Wild Boys (London: Calder, 1972). Wilson famously camped out on Hampstead Heath in his pre-fame youth.

[11] [64] Both in his “Retrospective Introduction” here and in his more recent The Angry Years.

[12] [65] Kingsley Amis, no friend of Wilson’s – he once proposed throwing him off a roof, as Wilson notes with some bemusement in The Angry Years — wrote much later that “Toynbee … after finding Colin Wilson’s The Outsider worthy of the highest praise … shiftily backtracked and condemned …. Religion and the Rebel, as a ‘vulgarizing rubbish bin’ unaware that it was actually part two of the same book…” Memoirs (London: Hutchinson, 1991), p182; quoted in Colin Stanley: Colin Wilson’s Outsider Cycle: a guide for students (Colin Wilson Studies #15); Nottingham (UK): Pauper’s Press, 2009.

[13] [66] It’s really very simple: “The media, at all levels, is a racket financed by monied interests in order to promote the policies and programs that are good for rich people.” Z-Man, here [67]. Outsiders – real ones, not the safe opposition promoted by the media – need not apply.

[14] [68] Hart will later note the tie between this and the alt-right, especially Jason Reza Jorjani.

[15] [69] “Outsider: Fascism and Colin Wilson,” Medium, July 8, 2017, here [70].

[16] [71] “The Outsider was an incomplete book” (p.1). Like Coppola, Wilson says there were other ideas he wanted to deal with in Religion and the Rebel that he did not have the space for in The Outsider. He intends to “probe deeper into the Outsider himself, while at the same time moving towards the historical problem of the decline of civilizations” (p.2).

[17] [72] “The Outsider is a symptom of a civilization’s decline; Outsiders appear like pimples on a dying civilization. An individual tends to be what his environment makes him. If a civilization is spiritually sick, the individual suffers from the same sickness. If he is healthy enough to put up a fight, he becomes an Outsider.” (pp.1-2).

[18] [73] The essence of Existenzphilosophie, according to Wilson, is “systematising one’s knowledge of how to live by the most rigorous standards – by the Outsider’s standards. Very few men can serve as examples of this kind of development.” Neville agrees: “For ultimate satisfaction man must find a principle which is for him a way of life, a principle which he can experience as true.” Freedom for All (1942), Preface.

[19] [74] Colin Stanley, loc. cit.

[20] [75] Wilson himself later admitted “there is simply too much in the book, and it is like an overstuffed pillow.” See “Afterword: Colin Wilson on The Outsider Cycle,” in Stanley, op. cit.

[21] [76] For example, The Law and the Promise (1961): “The purpose of the first portion of this book is to show, through actual true stories, how imagining creates reality… I want to express my sincere appreciation to the hundreds of men and women who have written me, telling me of their use of imagination to create a greater good for others as well as for themselves; that we may be mutually encouraged by each other’s faith. A faith which was loyal to the unseen reality of their imaginal acts. The limitation of space does not allow the publication of all the stories in this one volume.”

[22] [77] Freedom for All (1942), Preface.

[23] [78] Feeling is the Secret (1944), Foreword.

[24] [79] “Goddard Enterprises Ltd has been operating since 1921 and the elements of its success include Vision, Creativity, Expertise, Tenacity and Location.” Website here [80]. There is no apparent connection to The Goddard Group or Gary Goddard, who was accused of pedophilia in 2017 [81].

[25] [82] See Mitch Horowitz, ed., The Power of Imagination: The Neville Goddard Treasury (New York: Tarcher/Penguin, 2015), which not only collects ten of Neville’s short books, but reprints, as an introduction, the relevant chapter from Israel Regardie’s The Romance of Metaphysics (1946).

[26] [83] “Americans always assume a British accent means intelligence, so Sargon’s fans are being told they are right about the world, by a smart British guy, who sounds confident and reasonable. It’s why his clash with Spencer was a disaster for him. He was revealed to be a petulant, argumentative airhead.” Z-Man, “A Pointless Ramble About YouTube Stars [84],” January 10, 2018.

[27] [85] Lachman (“Historical Introduction”) says he “looked the part of the ‘young genius’.”

[28] [86] Though admittedly confined to a lecture at the Open Center in New York about twenty years ago, where Wilson put the audience of New Agers on edge by calling one of his Establishment foes “a right cunt.”

[29] [87] Consider Stephen King. In the MST3k episode “The Dead Talk Back,” a detective (who rather resembles Neville) contemplates a wall of book shelves, and one of the crew overdubs: “And on the shelf behind you every book Joyce Carol Oates released last month.” Oates is or at least was a fan of Wilson and provided an Introduction to a reprint of The Philosopher’s Stone, which was my own introduction to his work. I don’t recall who the publisher was, but a later reprint of Oates’ version is from Tarcher – the publisher slagged above for printing Napoleon Hill. Pulling it off the shelf to check the date, I see that I had it autographed by Colin Wilson in 1995, presumably at that Open Center lecture.

[30] [88] Alan Watts had similar motive, although he seemed able to achieve a better balance of lectures to books; on the other hand, it drove him to drink and possible his early death at 57; Neville lasted to 67, Wilson to 82, in line with his speculations in The Philosopher’s Stone on the relation between genius and longevity.

[31] [89] This is where Hart draws in the work of Jason Reza Jorjani; see Prometheus and Atlas (London: Arktos, 2016).

[32] [90] Well laid out by Jorjani in Prometheus and Atlas, Chapter Two.

[33] [91] Weirdly, it was The Occult (1971) that led Philip Toynbee to perform a second 180 turn and proclaim Wilson once more a genius; one might suspect these “respected critics” were simply desperately trying to one-up each other.

[34] [92] “What was needed was not some new religious cult but some simple way of accessing religious or mystical experience, of the sort that must have been known to the monks and cathedral-builders of the Middle Ages.” The Angry Years, loc. cit. Essentially the same as Watts’ tripartite historical scheme (see my review of Behold the Spirit, here [93]), with the Outsiders gradually becoming dominant in the Third Age of the Holy Spirit and demanding a suitable religion for their expanded consciousness; not surprising, since both rely on Spengler.

[35] [94] “The Outsider’s final problem is to become a visionary.”

[36] [95] See Colin Stanley, Colin Wilson’s ‘Occult Trilogy’: a guide for students (Alresford [UK]: Axis Mundi Books, 2013).

[37] [96] At Your Command, op. cit.

[38] [97] As we’ll later point out, Neville typically presents his teaching in the form of esoteric interpretations of Biblical stories; here, Luke 5:5.

[39] [98] Again, as will be noted, Neville disdains the literal interpretation of the text, and consequently the organized religions built upon it, insisting instead that it is an entirely psychological document meant to be applied to and by ourselves.

[40] [99] At Your Command, op. cit.

[41] [100] The Outsider, p.70; Wilson’s italics.

[42] [101] This chapter, “The Attempt to Gain Control,” is the one Wilson showed to Victor Gollancz, resulting in Gollancz offering to publish the completed manuscript.

[43] [102] Op. cit., p 321.

[44] [103] Wilson points out how Sartre had pointlessly sabotaged his philosophy by denying the reality of any such “transcendental ego.” Wilson, Sartre and Neville all agree, though, that there is no “unconscious” that determines or controls my life.

[45] [104] Freedom for All, Chapter One.