Which Traditional Britain?

Posted By John Morgan On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledThe problem with talking about tradition as applied to our present world, at least within the context of a people or a country with a long history, is determining what, exactly, tradition is, and which tradition to draw upon.

The idea of tradition as applied to a cultural or political movement can be a good one, since it offers something constructive to those to whom it makes its appeal. One of the main problems of the Right is that it is typically mostly, if not entirely, negative — Rightists always know what they oppose, but very often they don’t have much to say about what they actually want instead. As a result, modern Rightist discourse in Western Europe and North America has a tendency to be overly depressing, given that it only offers criticism — and sometimes, despair and pessimism — without any positive vision to accompany it. This is one of the major problems the Right must address, as this is surely one the main reasons why it has been so unsuccessful in recent decades. It’s not enough to know what we oppose; we must also know what we want.

This is a problem that those who regard themselves as being traditionalists in the United States feel particularly acutely, given that America is essentially a modernist revolutionary project with a past that only stretches back slightly more than two centuries. What is the American tradition? It is difficult to say. In lieu of a genuine national and cultural tradition that is rooted in the soil and in the people, as you have throughout Europe, all we really have is the myth of the “Founding Fathers,” who have been elevated to near-deity status in America today. While these men certainly possessed some admirable personal qualities, the extreme forms of liberalism they chose to base America upon lead more to a sense of uncertainty than of rootedness and tradition. This is why, when asked to justify America’s countless interventions around the world, an American will not usually appeal to history or to a sense of American identity, but will typically answer “freedom,” as if the meaning of the word in this context is self-evident. And, speaking from an American perspective, the answer is actually not wrong, for the philosophical essence of America as a nation is of freedom from any notion of tradition or identity beyond that of the individual.

One might say that, at the very least, the myth of the Founding Fathers, who were all of English origin, offers an idea of the ethnic and cultural traditions of the country. But given that the white Anglo-Saxon Protestant identity which first gave rise to America has long since been replaced by the idea of multiculturalism — first foretold by the idea of the American ‘melting pot,’ which dates back to the eighteenth century — and that the vast majority of Americans today, including most white Americans, have no connection to the WASP tradition in terms of ancestry, it is something that can only strike most Americans as something rather alien and estranging. A century ago, the Anglo-American ideal was the example which all immigrants aspired to emulate. This was most evident in the fact that, as in my mother’s family, recently-arrived immigrants considered it their duty to learn English as quickly as possible, and in fact, in most cases did not pass their native language on to their descendants. I’m sure it comes as no surprise to anyone here to know that many of the immigrants coming to America today do not share this view, and in fact stick to their native languages and cultures with vehemence — something they are in fact often aided in by the government and other institutions.

It might be assumed that at least an American of European descent today might be able to look back to his ancestors for a sense of tradition, the problem with this being that few of them today have any knowledge or interest in their ancestry beyond their immediate family. Today we have simply become “white” — which, in my view, is a meaningless and artificial term — and why I think the concept of “White Nationalism” is something that certain Americans are seeking to import into Europe, and which I feel should be resolutely resisted, as it would be the death of any genuine notion of identity and rootedness here. That’s a topic for another discussion. However, the rise of this concept of “whiteness” is hardly surprising given that the vast majority of European-Americans, including yours truly, are today of mixed ancestry.

To use myself as an example, if I wanted to embrace the traditions of my ancestors, I would find myself in quite a quandary. On my father’s side, I am of English, Welsh, Scottish, and German ancestry. My mother’s ancestors were ethnic Germans who emigrated from Transylvania at the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. My father’s American family has roots that extend back to Virginia in the early eighteenth century and North Carolina in the early seventeenth; my mother is from Ohio. Even if I were to only appeal to the places where I myself am from: I myself grew up in New York, and then lived in Michigan for nearly two decades before moving on to India for five years, and then Hungary. While I acknowledge my debt to each of these facets of my origins and background, the traditions that each of these places represent are quite different from one another, and it would be impossible to choose to identify with one exclusively without doing a disservice to the others.

This type of uprootedness, which one might call an almost nomad-like existence, is not restricted to America but has spread across the world. Indeed, one could say that this sort of atomized existence is the essential factor of postmodern life. Perhaps in a sense it is true, as the French newspaper Le Monde stated on September 13, 2001, that “we are all Americans now.” The archetypal individual of the twenty-first century is an American.This problem is similar to what I see as the one confronting any attempt to define a traditional Britain in the postmodern world we now find ourselves in. The question that first springs to my mind when I hear of a traditional Britain is, “Which traditional Britain?” It seems to me that there are many traditional Britains to choose from. Unlike America, fortunately, the peoples of Britain have rich cultural, national, and ethnic traditions to draw upon to inform their sense of identity. Even if many of the British seem uninterested in this today, it is at least something real that can potentially be drawn upon.

Still, the issue of which tradition seems like a very palpable problem to me for anyone who is looking to use tradition as the basis for action in the present. And there are many traditional Britains to choose from.

If we turn the clock back to the Britain of a century ago, we would find it at the height of the British Empire, governing more than four hundred million people over a quarter of the Earth’s surface, with a Church of England very different from the one we know today standing secure as one of the pillars of British social life. If you were to ask my advice, this is not the traditional Britain that I would aspire to restore, given that the political structures that all empires inevitably give rise to the displacement of culture and ethnicity as the unifying forces of the countries which govern them, thus setting the stage for multiculturalism and mass immigration as we know today. I will likewise quote the Italian traditionalist Julius Evola concerning the British Empire, when he wrote concerning it in the 1930s [3] that:

England possesses a monarchy, an almost feudal nobility, and a military caste which, at least up until very recent years, showed remarkable qualities of character. But all this is mere appearance. The real centre of the “Empire” is elsewhere; it is, if we may put it this way, within the caste of merchants in the most general sense, of which the modern forms are plutocratic oligarchy, finance, and industrial and commercial monopoly. The “Shopkeeper” is the veritable master of Britain.

While the Empire achieved great things, we must recognize that the sickness of liberalism was already very far advanced during its day.

If we go back five hundred years, we would find ourselves in the Britain of Henry VIII, with the Crown being more concerned about wars with France and with the Scots than with conquests on the other side of the globe. This Britain was still firmly within the fold of the Roman Catholic Church — even though this was soon to end — which laid the earliest foundations for a common European cultural identity.

If we go back a thousand years, we would find England on its own, with the idea of a United Kingdom for all of Britain as something still inconceivable, and with its primary foreign policy considerations being how to deal with attacks by Vikings.

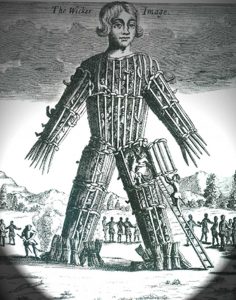

And if we go back a thousand years prior to that, we would be in pre-Roman Britain, with the prehistoric Celts still organized tribes and practicing the religion of the Druids, who adhered to the doctrine of reincarnation according to Julius Caesar.

At the other end of history, if we were to try to identify the tradition which currently holds sway in England, we would have to point to the legacy of positivism, empiricism, and the analytic school — the philosophical schools of thought most closely identified with Britain, all of which have been wielded as the most powerful intellectual wrecking balls hurled against everything traditional ever devised by man.

Parallel to this, the two ideologies which predominate in the world today are liberalism and capitalism — both of which were also born out of the British intellectual tradition. Granted, today these ideologies are being propagated and imposed on the rest of the world primarily by Britain’s American stepchildren, but a contradiction that any British (and also American) traditionalist must face is that the very liberalism that is the archenemy of Traditionalism is a part of the very tradition that we ourselves spring from.

So, as one can see, if one claims to represent a traditional Britain, there are quite a range of institutions and belief systems that one must accommodate. Of course it would be ridiculous to try to unite all of this into one, overarching worldview, but at the same time it is important that we acknowledge that all of these elements are a vital part of the British tradition and that this tradition would not exist without all of them. We are not therefore obliged to accept all of them equally, of course, but our understanding of Britain would be incomplete if we were to leave any part out. Even the philosophy of liberalism, for all its flaws, can offer us insights if we take it in the proper context.

But even if we make peace with the idea that the British tradition contains many disparate and even contradictory elements if taken as a whole, some of which are hostile to the very idea of tradition itself, this leaves us with the question of which tradition should British traditionalists look toward to guide them as they contemplate the course Britain should take in the future. I think it is worth pointing out that the idea of “choosing a tradition” is in itself a thoroughly modern notion — until very recently in history, one was simply born into a tradition, and few ever seriously contemplated adopting one that was significantly different from what they had grown up with. Nevertheless, I think we should see this as a positive aspect of the modern world, since although today people in the West are often born without roots, we have the ability to survey the available traditions critically and choose one that is ideal for our particular needs.

The most important thing to bear in mind is that we should not give in to the temptation to overly fetishize any one historical era, and thus focus our energies on trying to restore it. We should not, like Gatsby, simply try to repeat the past in a quixotic fashion. Even if this were possible, which it isn’t, we would just be condemning ourselves to repeating not only the aspects that we like about a particular era, but also to repeating all the same mistakes which have brought us to our present predicament.

This is personally why I never apply the word “conservative” to myself. This is partly because the people who typically use the term these days tend to belong to the false, liberal Right that participates in the meaningless spectacle that passes for politics in Britain and the United States these days. Its only role in recent decades has been to gradually cede ground to the Left and provide the illusion of opposition. Indeed, I would propose that instead of the outmoded dichotomy of Left versus Right, that today the opposition of liberal versus anti-liberal is far more meaningful method of classification for political parties and ideologies. I personally prefer the term coined by the Italian traditionalist Julius Evola, who referred to the “true Right,” which he once defined as those who accept “those principles which were accepted and seen as normal by every well-born person everywhere in the world prior to 1789.”

As for conservatism, there’s little in the modern West that I think is worth conserving — what is good in it today is mostly happening in spite of the dominant social trends rather than because of them. Most of what once made the West something great was already destroyed some time ago, or is rapidly decaying. There are certainly many things from our past that I think are worthy, in fact vitally so, of being conserved, but the answer is not to become a nostalgic. What is needed is not conservatism, but radicalism: the creation of something new that is in keeping with what was healthy and good from the old.

We shouldn’t be afraid to use the term radical. I consider that traditionalists are indeed radicals, but not in the way our opponents see fit to portray it. We understand that the days of throwing bombs and of throwing up barricades in the streets as a means for political change are a thing of the past. The West has progressed beyond the need for such things — and we are all the better for it.

Traditionalists are radicals in that they don’t think it is enough to merely see a changeover in political leadership every few years or to adjust taxation policy. We understand that, to meet the challenges that the West currently faces, we must rethink our understanding of the suppositions on which our society is currently founded. Are all individuals genuinely created equal? Should economics be the basis of all aspect of social life? Is multiculturalism a positive thing for a society to embrace? Can we reconcile the notion of an ethnic identity with liberal capitalism? Is a strong central state in such chaotic times still the best way of organising society, or should we perhaps consider distributing more power to local communities in loose confederations? Are ‘rights’ something we are all inalienably imbued with from birth, and if so, who defines them? Is secularism really the best foundation on which to base a society that can imbue its citizens with higher meaning? Is the best way to help the Third World to “invest” in it — which generally means exploiting its cheap labor and resources and hoping that the resulting profits somehow trickle down to those at the bottom? Do we have an obligation to spread democracy, Western popular culture, and capitalism to every corner of the globe? Such questions are never asked in the current political debate.

Since I have been using the term Traditionalism a lot, I feel I should mention the meaning that some on the Right have given it in recent years, which is in reference to the teachings of the French philosopher, René Guénon, and his Italian colleague, Julius Evola. In this form of Traditionalism, the concept of “Tradition” — spelled with a capital T to distinguish it from tradition in the usual meaning of the word — is used to describe a metaphysical core which they posited exists at the heart of all the world’s religious traditions. In essence, Traditionalism is the idea that there is a single, metaphysical Tradition emanates from the core of reality, which one could term God, and that these emanations manifest differently in the material world, depending on the time and place in which they manifest as a result of this divine revelation. According to traditionalist doctrine, this is the origin of what are sometimes called the “great religions,” including Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, Christianity, and Islam. In Traditionalism, while the metaphysical basis of all the religions is one, this truth manifests differently depending on the cultural and temporal particularities of the place and time in which it appears — thus, a particular religion may be appropriate for a particular people and a particular place, but not for anyone else. The great English poet William Blake expressed a similar sentiment when he wrote, “The Religions of all Nations are derived from each Nation’s different reception of the Poetic Genius, which is everywhere call’d the Spirit of Prophecy.”

In the traditionalist understanding of things, individuals adopt a religious practice in order to connect themselves with what I will call, after Julius Evola, the Primordial Tradition, which lies at the basis of all reality. Traditionalism also follows the doctrine of the cycle of ages, which was common to many ancient cultures, including those of Europe, and which runs contrary to the modern idea of progress. This doctrine holds that time unfolds in a manner that proceeds from a golden age, marked by nobility, to the gradual arrival at a final age of degeneracy, after which the cycle ends and then repeats itself. As such, believing that we are currently in the darkest age, traditionalists seek to preserve what they can of the higher ages and the knowledge of what is eternal amidst the fallen times we live in. As such it taps into the very essence behind what those of us on the true Right are attempting to do: be the men among the ruins of modernity who prepare the way for the return of the golden age.

What is the use of Traditionalism for those of us here, you may ask? In essence, Traditionalism is the most radical idea in the world today. It recognizes value in established beliefs, customs, and values. It makes no compromises with the modern world whatsoever. One might even say it goes too far in its rejection of the world as it is, in some respects. Nevertheless I think its perspectives are valid. It is also useful in that, positing a unified origin behind the various religions and cultures of the world, it offers a basis for viewing all who work against the current of liberalism as fighting in a common cause, and thus promotes unity rather than division among various religious and ethnic communities, both within our own circles and across the globe. Traditionalism stands for the validity and the value of all traditions. In this, it may sound suspiciously like multiculturalism, but the difference is that in recognizing the validity of all traditions, it simultaneously defends the importance of maintaining them in their uniqueness — thus there is no allowance made for the construction of a “universal” culture or religion that merely picks and chooses what it needs from the world’s diversity and discards the rest. Tradition, in the Guénonian sense, defends the need for the small-t traditions as well. Thus, it provides a common cause for the Christian to work alongside the pagan, or for the English nationalist to work in alliance with the Persian nationalist (for example). Likewise, I believe that adherence to Tradition charges one with the need to act as a steward of the Earth, our natural home. As Roger Scruton has written, Green issues are inherently a Rightist issue, not a liberal one, and this is something that the true Right should look to integrate as it looks for ways to become relevant again in the postmodern world we live in.

Likewise, Guénonian and Evolian traditionalists believe that, in accordance with the teachings of all the world’s great religious traditions, the only valid form of government is a monarchy supported by a church. Given this view of things, I suspect that Evola would probably say that the Britain of the Middle Ages, before Henry VIII’s split from Rome, was the high point of the British tradition.

I wish to add that while I see Traditionalism as an idea of great interest and potential, I am not someone who thinks that we have to see Tradition as a static thing that has to be constantly reiterated in the same way and in the exact same style as it has before, as it is understood in some quarters. Cultural forms, like reality itself, are constantly evolving and changing, and we shouldn’t always fear the new (although neither should we accept it unreservedly). And I think the Traditionalism of Guénon and Evola also puts its adherents into an uncomfortable quandary since it rejects Protestantism on the grounds that it is a man-made heresy; European paganism on the grounds that they are dead traditions that cannot be reconstructed; and even regards modern Catholicism with suspicion due to its modern and liberalizing tendencies in recent years. That really doesn’t leave much. While they make valid points about the problems inherent in each of those traditions, I think they are too absolutist in their rejection of any possibility for restoration, or for what value they might be able to bring to individuals or small groups. Taken at their best, I think certain aspects of Protestantism or modern paganism could be excellent vectors to get people back in touch with their roots and with tradition — both large and small “t.”

I also think the traditionalists’ extremely dire prognosis for the modern world, which basically boils down to withdrawing it from it as much as possible, tends to cultivate apathy and pessimism in people. While our situation in the modern world is bad, it is not hopeless, nor is it without merits. For example, two of the greatest traditionalist (in a non-doctrinal sense) artists of recent decades for me would be the filmmakers Andrei Tarkovsky and Hans-Jürgen Syberberg. They were operating in a medium which is entirely a product of modernity in every way, and which, admittedly, most of the time is used for degenerative purposes. And both of them, Syberberg in particular, are not only filmmakers, but avant-garde filmmakers who used highly unorthodox methods of a style that were often similar to that of the heights of “liberal” cinema (Surrealism, the French New Wave and so forth). And yet for me, Tarkovsky’s Stalker, Nostalgia, and Andrei Rublev, as well as Syberberg’s film of Wagner’s Parsifal, rank as some of the most spiritual works of art I have ever experienced. I think they communicate the essence of what Tradition is, even though they are entirely modern in conception and assume a form that is non-traditional. If something can convey such an experience of meaning, or open up new vistas of meaning and new ways of viewing reality, then it’s good in my judgement, even if it may be unorthodox. The modern itself can be used to undo, or perhaps alter is more accurate, itself. What is needed is not simply an obsessive desire born out of fear of the new to return to an earlier time, but a recasting of the modern in keeping with the values of that which is timeless. This is what the French “New Right” author Guillaume Faye has termed archeofuturism. And I think that this provides a sound basis for the sort of work that those of us interested in tradition want to do in order to bring about a new and better civilization.

As a side note, I’ll just mention the interesting fact, in case some of you aren’t aware, that Prince Charles, as some of you may know, is the patron of the Temenos Academy here in Britain, which is today perhaps the largest explicitly traditionalist institution in the world — it certainly is in the English-speaking world. It certainly speaks well of the future of the British monarchy that its future King supports the traditionalist worldview.

So while I have great respect for the traditionalists, I think we should not see them as the last word on the subject of tradition. There is another view of tradition that I think is worth mentioning, and that is the concept of “traditionism” that was coined by another Frenchman: Dominique Venner, the historian and veteran paratrooper of the Algerian War and the OAS who infamously committed suicide in Notre Dame Cathedral in May 2013 as a protest against mass immigration and the increasing liberalization of France. I will quote Venner himself [4] by way of definition:

Every great people possesses a primordial tradition that is different from all others. It is the past and the future, the world of the depths, the bedrock that supports, the source from which one may draw as one sees fit. . . For Europeans, as for other peoples, the authentic tradition can only be their own. That is the tradition that opposes nihilism through the return to the sources specific to the European ancestral soul. Contrary to materialism, tradition does not explain the higher through the lower, ethics through heredity, politics through interests, love through sexuality. However, heredity has its part in ethics and culture, interest has its part in politics, and sexuality has its part in love. However, tradition orders them in a hierarchy. It constructs personal and collective existence from above to below. . . . Tradition is not an idea. It is a way of being and of living, in accordance with Timaeus’ precept that “the goal of human life is to establish order and harmony in one’s body and one’s soul, in the image of the order of the cosmos,” which means that life is a path towards this goal. In the future, the desire to live in accordance with our tradition will be felt more and more strongly, as the chaos of nihilism is exacerbated. In order to find itself again, the European soul, so often straining towards conquests and the infinite, is destined to return to itself through an effort of introspection and knowledge. . . . For Europeans, living according to their tradition first of all presupposes an awakening of consciousness, a thirst for true spirituality, practiced through personal reflection while in contact with a superior thought. . . . Taking notes, reading, re-reading, learning, repeating daily a few aphorisms from an author associated with the tradition, that is what provides one with a point of support. Homer or Aristotle, Marcus Aurelius or Epictetus, Montaigne or Nietzsche, Evola, or Jünger, poets who elevate and memorialists who incite to distance. The only rule is to choose that which elevates, while enjoying one’s reading. To live in accordance with tradition is to conform to the ideal that it embodies, to cultivate excellence in relation to one’s nature, to find one’s roots again, to transmit the heritage, to stand united with one’s own kind. It also means driving out nihilism from oneself, even if one must pretend to pay tribute to a society that remains subjugated by nihilism through the bonds of desire. This implies a certain frugality, imposing limits upon oneself in order to liberate oneself from the chains of consumerism. It also means finding one’s way back to the poetic perception of the sacred in nature, in love, in family, in pleasure and in action. To live in accordance with tradition also means giving a form to one’s existence, by being one’s own demanding judge, one’s gaze turned towards the awakened beauty of one’s heart, rather than towards the ugliness of a decomposing world.

I find this idea of tradition from Venner quite compelling, and a much more refreshing conception than we usually find in the Guénonian traditionalists. Venner’s key insight is that, while we can acknowledge the value in other traditions, those of us who want to remain engaged with the life of our society and our civilization should stay close to home in terms of the traditions that we seek to integrate into our lives. And he also understood that tradition is something that must be lived daily, and not simply discussed in cafes and on social media.

Along these lines, I strongly encourage anyone here who wishes to stand for a traditional Britain, and who has a skill or a creative urge of any type, to try to think of ways to apply this toward actualizing the beliefs that you hold dear. If you’ve been thinking about a book of some sort, write it. If you can play music, play it. If you want to plant a garden so that you can become self-sufficient and less dependent on the system that you dislike, do it. By doing these things, we both render ourselves as examples to others and also build our own characters. Real revolution does not really happen on battlefields or in government buildings, but within the souls of each person who desires it. No other change is possible before that occurs.

It is vitally important that we must embody the traditions and ideas that we uphold. This is as much a cultural matter as anything else I have just discussed, and perhaps more so. And this has been a real problem on the Right for a long time. So many people who proclaim themselves the leaders of our “movement” either embarrass both us and themselves with their hypocrisy. In the worst cases, they actually set us back by embroiling themselves in scandals that only blacken all our names and confirm everything that our enemies say about us. It is not enough to espouse the right ideas, we must act on them and live them, and base all of our actions in life upon them, or else everything else that we are attempting to do is destined to failure. The political struggle is only the outward form of a battle that is really more cultural, and culture rests on what lies within the soul of each individual who participates in it. In order to build individuals willing to sacrifice the comforts of modern life for the sake of an ideal, a solid sense of identity and purpose must first be present. Once we have achieved that for ourselves, we will provide an example that others will strive to imitate.

I’ve said quite a bit now about what tradition means for the individual, British or otherwise. But to return to the idea of a traditional Britain, in closing I’ll say that regardless of what happens, the Britain of the future will not be anything like the past, nor anything like how either liberals or traditionalists might imagine it now. History always surprises us. Should British traditionalists succeed in their endeavors, the tradition of Britain’s future will nevertheless not be identical to anything from its past, even if they must keep the memory of all aspects of Britain’s past alive in their minds and actions. There is no single correct traditional Britain that should be called upon.

Speaking as an outsider, what I would like to see in a future Britain that is reborn out of its traditions would be one with a renewed sense of and confidence in its national and ethnic identity, purged of liberal fallacies and based solidly upon those ancient virtues which made England great in the first place. The hands of the monarchy should also be untied and placed over the rule of international corporations and bankers, and the sacred should be cultivated and allowed to resume its place at the center of British life, as it once was. At the same time, I would hope to see Britain continue to develop a European identity alongside its British one so as to form a united European front against the challenges of the future, as well as to avoid the mistakes which led to so much bloodshed in the past. And most importantly, and I say this as an American, a traditional Britain will need to get free of the influence of America and NATO, and resume pursuing its own interests rather than kowtowing to the ill-conceived whims of Washington and its corporate masters.

I urge you to embrace your identity as a traditionalist, for it is the work that we are doing today — much of it only cultural or intellectual — which is building the superstructure that tomorrow will be housed in. Our opponents see this and they are terrified. People across the West are growing weary of the hollow promises of liberals. I firmly believe that the cultural vigor of the West as a whole is passing, if it hasn’t already passed, from the liberals to the traditionalists. When they call you names, understand that it is merely an act of desperation by which they hope to delay your ascendancy for a short time longer, and nothing more. They know that their game is nearly up. They won’t last any longer than a snowflake in the tropical Sun when the world they have built upon their concoctions collapse before the onslaught of history. Their words may sting you today, but tomorrow belongs to you.

I’ll close by quoting William Blake’s call to Britain [5] to restore its lost Golden Age in the hope that, as with much of his work, it is prophetic:

England! awake! awake! awake!

Jerusalem thy Sister calls!

Why wilt thou sleep the sleep of death

And close her from thy ancient walls? . . .

And now the time returns again:

Our souls exult, and London’s towers

Receive the Lamb of God to dwell

In England’s green and pleasant bowers.