Henry Williamson & T. E. Lawrence

Posted By Margot Metroland On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,114 words

December 1st is the 122nd birthday of Henry Williamson (Dec. 1, 1895–Aug. 13, 1977), English naturalist, novelist, and nationalist.

One of Williamson’s unique distinctions is to have been T. E. Lawrence’s literary friend and personal confidant during the last seven years of Lawrence’s life, 1928–1935. It is a matter of record that when Lawrence had his fatal motorcycle accident, he had just been to the post office to send a telegram to Williamson. (Near end of excerpts, below.) The plan was to meet the following week and discuss Williamson’s proposal to start an ex-servicemen’s organization in the cause of European peace.

These years were Williamson’s noontide of fame, as novelist and essayist, and they were his friend’s most obscure — quite deliberately. For most of this time Lawrence was serving as an aircraftman in the R.A.F., in which he had enlisted in 1925 under the name T. E. Shaw in order to find a measure of privacy and peace of mind, unencumbered by his international fame as Lawrence of Arabia. Shaw/Lawrence served in India 1926–1928, and afterwards in England near Plymouth and Southampton. It is during this latter period that Lawrence first visited Williamson at latter’s farm near Georgeham, north Devon.

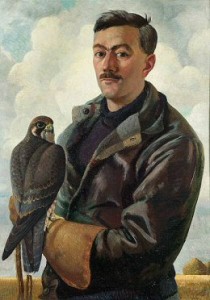

Threnos for T. E. Lawrence [1], excerpted below, was written in 1954. It is less an intimate portrait than a somewhat dreamlike, impressionistic recollection by an admiring acquaintance. Having known of Lawrence as a heroic figure for years before he met him, Williamson is always trying hard to disentangle Man and Myth.

Their friendship had begun by correspondence in 1928. Williamson sent Lawrence a copy of his recent Tarka the Otter, which was about to win the Hawthornden Prize. From India Lawrence replied with his appreciations, along with some condescending advice on how to write; followed by much embarrassment when he discovered that the prize-winning Williamson was indeed an established writer, not some lucky newbie.

Back in England a few months later, Lawrence proposed to drive up on his new motorcycle to pay Williamson a visit. This was a trip of eighty miles each way. Not surprisingly, the visit was repeatedly postponed. But not forever:

On 2nd July 1929 a letter.

‘If it rained at your end as it did here, all yesterday, then this letter isn’t needed to explain my defection. Only if the sun shone brilliantly, and your hay is made, I must apologise. It was quite impossible for pleasure riding. I can ride (at 30) on a wet road: but that’s transport, no sport. Riding gets pleasant in the 40-50 range.

‘Yours, T.E.S.’

I wrote and asked him if he would be going to the R.A.F. display at Hendon, saying that I was going, during the same visit to London to the award of the Hawthornden Prize for that year. It was to be given to Siegfried Sassoon for his Memoirs of a Foxhunting Man. I offered to take T.E. to the R.A.F. show in my car, but he replied that it would not be fast enough to get him there and back.

‘Noon Sat. to midnight Sunday is so short a week-end, but it is all we get, without special permission, and the seeking that sticks in my throat . . . if you see Sassoon to speak to, tell him that his book (novel) pleased me: but I’d lose it all for his worst poem.

‘All Quiet on the Western Front is the screaming of a feeble man. It will not last as long as Tarka except as a document. Do not distress yourself about “lasting”: not even our bones do that, except momentarily. I think that to last is only to be in doubt longer.’

A postscript said he would try and reach the village on 28th July, if I would be there.

Lawrence meets Williamson

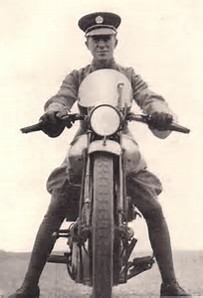

T. E. Shaw astride the cycle.

In the evening of 27th July the dulcet tones of the BBC foretold a deep depression approaching Ireland and our South-West Coast from the Atlantic. Towards midnight the rain began to drive against the southern window of the writing room, and I went to bed saying to myself that he would not come. In the morning it was still raining, and I thought of the eighty-mile journey from Plymouth across Dartmoor in the midst of a driving rain, and the narrow twisting roads and lanes, many of them untarred, grey slippery surfaces. It rained and it rained . . . The clock in the church tower a gunshot away (sometimes in boredom I used to fire through the writing-room window at the weathercock, just out of damage range) struck twelve times. I got up and looked out of the window and saw below a red face under a peaked blue uniform cap, intensely blue eyes, short body enclosed in glistening black astride a large nickel-plated motor-cycle showing in the lane outside. As the bike stopped a rubber foot was put on the ground and the cap peak pushed up slightly. After a swift mutual grin I opened the garden door and ran down the steps. He pulled the Brough [cycle] on its stand.

‘Hullo.’

‘Hullo. I had to come. I found myself developing a complex about it.’

‘So was I. Will you put the bike in the shed?’

‘No thanks. I must leave at half-past one.’

‘You shall. That’s a fine storm-suit.’

‘It was designed for mine-sweeping during the war—no longer made.’

They sat and talked. A remembered snippet of conversation:

T.E.: ‘Have you had any Americans calling yet to see the greatest living descriptive prose writer in English?’

This was slightly startling; I didn’t know what to make of it, except to be amiably reticent, non-committal.

‘You will. And to the first fifty or so you’ll look very modest and droopingly acquiescent, and you’ll murmur a mixture of thanks and self-deprecation: to the fifty-first you’ll probably say “Balls”. That’s the only way to keep a sense of self-criticism. If you don’t you’ll become like Bernard Shaw, believing only the nice things said about you . . .’

* * *

On impulse I bought passage to America. Was there hope in the New World, I wrote to ‘T.E. Lawrence’, saying I was leaving England. As I was packing two mornings later, a reply came.

‘. . . I hope you will not hate the U.S.A. So many people do, whereas it all sounds to me so strong and good. Canada less so, but then I like towns, because only by contrast with cities do trees feel homelike, or seas look happy.

‘Will they send this rot on? Probably not…’

Williamson in New York

New York: the young, keen writers and critics, pleasantest people in the world, so eager to know, to understand, and share; new York, moon-strange Broadway: sidewalk fatigue of Manhattan, night and day being one, great skiey cliffs of light and running avenues of fire far down below . . .

The old version of The Dream of Fair Women [2] was rewritten in three weeks, in an empty eyrie downtown, overlooking Sheridan Square. Let them say what they like about a book written in three weeks; slashing into hour after hour, day after day, night after night, one knew what was being done, although one didn’t know how it was done. Afterwards life was empty, an aimless wandering through canyons of light and noise and disintegration until S.O.S. calls brought Loetitia [Mrs. Williamson] from England, and home again in the dirty Leviathan . . . how was my alter ego? Would a short letter be an intrusion? it was risked.

‘Your letter made me pump the tyres of the neglected bike, with a view to seeing you at once . . .

‘It is immoral to write in working hours.

‘I wish I could have seen New York without being seen.

‘T.E.S.’

“I’m Cunard Publicity, May We Take a Photograph Please?”

A few years, letters, and visits later, Williamson decided to go to America again, this time on a trip to Georgia and Florida. He was sailing from Southampton. Aircraftman T. E. Shaw was stationed nearby.

The Berengaria was to sail at noon on the last day of February, 1934. After missing each other in my cabin, we both went to the gangway as the key-position on the boat.

He was standing, hands behind back, patiently, against a bulkhead. He wore overalls, splashed with the sea. His face was brick-red, his eyes cornflower-blue. He looked like an elder, more serious brother of the man I’d talked to . . . five years before . . . He had thrown off his Joseph’s coat of many colours, the chameleonic intakes, the labels and theories of perplexities of his many acquaintances about himself, men lesser in penetration and speed of sight. He had ceased to be ‘a rare beast, will not breed in captivity’ which Winston Churchill, that brilliant exponent of ‘public opinion’, had insisted he must be.

I had brought half a bottle of champagne for J. H. (another visitor), and one of tomato juice cocktail for T.E. T.E. said . . . ‘Thanks, but I daren’t drink anything. One sip, and I go all dithery, and utter the most awful rot’. . .

While we were talking someone came diffidently to Lawrence, and said, ‘Excuse me, I’m Cunard Publicity, may we take a photograph, please? Of course I understand if you’d rather we didn’t . . .’

‘It would get me into trouble,’ replied T.E. Shaw, indicating his uniform, while J.H. and I started to talk to each other about each other. ‘They don’t like individual publicity, I am sorry, but I must say no.’

‘Of course, sir, I understand,’ and the young man raised his hat and rejoined two of his friends who stood by a tripod and camera and sound apparatus among the passengers saying good-bye to their friends. Eyes were now turned upon T.E. Lawrence.

He seemed to be fading. He was fading. He was dulled out.

* * *

The Last Year

The world knows the end of the story. But let me hold my thread of the tapestry of human friendship for a little while longer. T.E. Shaw was discharged finally from R.A.F., and went to live at his cottage on Egdon Heath [actually Clouds Hill, Lawrence’s home in Dorset]. At once he set tow work with his hands, completing a glass-covered swimming bath among the rhododendrons, and beginning the building of a small bungalow near it for the use of a friend, a local man who helped with the gardening and work about the house: Crusoe and man Friday. Was he happy? No man, working with his hands, is unhappy. Not for him the worried brow of responsibility, the hollowness of political position, the wrinkled foreheads of the white faces of Whitehall. In the peak of his power he had measured himself against the world’s leaders at Versailles; and seen nothing there, except selfishness, finesse, and frustration . . .

How the family man [Williamson is here referring to himself], with a hundred domestic details to distract and irritate him every day, dependent on an unnatural practice of sitting still several hours out of the sun, forcing his vitality into his brain and striving to imagine things, to be turned into words, words, words: for money — how he envied the freedom of T.E. Shaw!

So one May morning he flung down his pen and went to the garage, and looked at the long low length of the Alvis car. Better first to send a letter: or simply to turn up: which? He wrote a letter. Now this was quite an occasion, he thought—perhaps the beginning of a friendship that…for it was time something was done about the pacification of Europe through friendship and fearless common sense. The spirit of resurgent Europe must not be allowed to wither, to change to a thwarted rage of power. With Lawrence of Arabia’s name to gather a stimulation to cohere into unassailable logic, the authentic mind of the war generation come to power of truth and amity, a whirlwind campaign which would end the old fearful thought of Europe for ever. So that the sun should shine on free men!

He must go at once to Egdon Heath and tell the only man in England who could bring it about. So he wrote a letter saying he would arrive and bring his own food.

The answer came by telegraph.

‘11.25 a.m. 13 May 1935

‘Williamson Shallowford Filleigh

‘Lunch tuesday wet fine cottage 1 mile north Bovington Camp

‘Shaw’

Returning on his motor-cycle from the Camp post office, whither he had gone specifically to send that telegram, ‘T.E. Lawrence’ crashed and broke his head, and knew nothing more, save of strange suns beyond Arabia, beyond the human shores of the world.

Notes

1. Henry Williamson, Threnos for T. E. Lawrence. Henry Williamson Society, 1994.

2. Henry Williamson, The Dream of Fair Women: A Tale of Youth after the Great War. Revised edition, 1931.